High School

In my senior year I took tests to see if I could qualify for the Navy ROTC or the Army

Specialized Training Program (ASTP) I thought the Navy would be more exotic but I was

worried about water splashing on my glasses. I therefore selected the ASTP because of that,

although I was accepted by both programs. This decision was typical of my ignorance at the

time. The Navy guys stayed in college the entire war. The ASTP ended up in the Infantry.

Induction

I reported for induction on August 11, 1943, 2 days after my 18th birthday. I went to Fort

Sill and reported in that afternoon. A wait of over an hour for something to happen was my first

experience of Army efficiency. I was finally taken to a large room full of bunks and people;

probably 60 double bunks in neat depressing rows. Nobody was in uniform as yet. I however

had a khaki outfit I was proud of because I thought it made me look like a soldier. It turned out

that was the case. I was pulled out of the place, put on a truck and went to the mountains to help

fight a forest fire. Before I had to actually do anything, a Lt. noticed my civilian shoes,

questioned me, ate me out and sent me back to camp.

The following day I went through the induction routine. We went naked through a long

line for various humiliating inspections. The man behind me was obviously a full-blooded

Indian who also obviously had his penis cut off. I don’t know if he was accepted but the rest of

us passed. After that we were sworn in. I then took a written test and was questioned by a

Psychiatrist? . He informed me that I was only mediocre soldier material. I don’t recall why he

told me that but I hoped to prove him wrong. Events probably proved him correct. (He probably

said average instead of mediocre but I thought I was way above average.)

My first experience with KP occurred at Fort Sill. I was given a large barrel of boiled

chicken and was required to tear them into smaller pieces with my hands. It ruined my appetite

for chicken for some time.

Basic Training

A group of about six of us was ordered to Ft. Benning, Georgia. (The Infantry School)

In spite of my “Mediocre” capabilities, I was put in charge of this detail. We went by civilian

trains. My being selected to lead this and many other details were a common occurrence. I

finally decided it was because I wore glasses and looked smarter than the other dodos. Anthony

Hillerman, the famous author, was one of this group. I strutted up and down the aisle of the train

with all civilian eyes admiring me (I thought). It turned out I was wearing my helmet liner

backwards. The train went through exotic country I had never seen before and I thought I was

the luckiest guy in the world to get to do this.

The barracks at Fort Benning were tar paper shacks with the usual double row of double

bunks with a latrine on one end and the sergeants quarter on the other. We learned military

courtesy, (how and who to salute etc.) And marching, marching, marching. The days started

before sunup with much whistle blowing and hollering. I thought it was great. (Temporarily)

Physical conditioning of many types were performed constantly. This was not fun.

The squad I was assigned to and perhaps our entire training company was all assigned to

the ASTP. We would go to college after the training. My squad was nearly all from Oklahoma.

It contained Hillerman, Huckins and several others whose names I don’t remember. I made the

mistake of writing to the base newspaper stating us Oklahoma soldiers were superior in every

way to other groups. It unfortunately was published and I was besieged by several other groups

taking up the challenge. It then turned out I was the only one from Oklahoma and had to eat

crow. I was then questioned by an unknown officer who apparently decided I was still not officer

material. He was looking for OCS candidates.

Basic training at the Infantry School was different from most. We had to be familiar with

all Infantry weapons and had to qualify with most. .

I did very well at all the shooting qualifications, although I broke my glasses on the way

to the rifle range. I was allowed to take it over when I got my glasses replaced. I did not do well

at the pistol, which led me in later civilian life to buy an Army 45, join a gun club and try to

master the pistol. I never did.

We were then given written tests again, asked where we wanted to go to college, what

branch of the service we preferred. We ALL asked for the Air Corps. Many asked to be sent to

prestigious eastern colleges. All the Oklahoma people were sent to Oklahoma A&M for

Engineering courses. We were to be commissioned when and if we graduated.

Oklahoma A&M

I never seriously studied when I was in high school. I was immediately over my head in

these Army classes. It was a very heavy class load and I could not keep up. I took free time

tutoring in an attempt to grasp it. My problem was that I had not had plain geometry in high

school and the courses I was taking were based on the assumption I had. It made trig. and other

advanced math classes almost incomprehensible. (I had to take geometry my senior year in

college at no credit. (At OU) It turned out that is a requirement to even get admitted to college. I

did not flunk out at A&M but I was miserable and requested a transfer (To the Air Corps). This

request was refused. One math course I took turned out to be of great help to me in the Army

and later in life. That was Ratios.

The exams at A&M were usually multiple choice, with four possible answers. The tests

were designed to not be finished. On the final exams (Before being sent to the Infantry), I

worked as far as I could and then working with ratios on the answers, I finished the entire test. In

chemistry, I scored the highest in the school and was very high up in all the courses. Amazing

Due to heavy casualties in Europe, and a severe shortage of cannon fodder (Infantry), the

ASTP program was disbanded and the troops sent to Infantry Divisions. We were again asked

what branch of the service we preferred. My request and everybody else’s were ignored. I even

volunteered for glider pilot training. (No glasses) Most of us, including Hillerman were sent to

the 103rd Infantry Division in Camp Howze Texas. This is near Gainesville in north Texas.

103rd Division

(Spring, Summer & early Fall of 1944)

103rd Division

(Spring, Summer & early Fall of 1944)I was assigned to the 1st squad of the 1st platoon of B Company

of the 410th Regiment of the 103rd Division. This is a rifle squad. A

rifle squad at that time consisted of 12 men. A squad leader (Staff Sgt.),

an assistant squad leader ( Sgt.) and 10 riflemen. Three of the riflemen

were the B.A.R. team, two were scouts and the others were ordinary

riflemen. All were equipped with the M1 Garand rifle except the BAR

man, who carried the Browning Automatic Rifle. This is a hand held machine gun equipped with

a bipod that is fed with 20 round clips. It weighs 22 lbs. empty. I was later to be assigned this

job. This entitled me to get promoted to the high rank of PFC. The other two members of the

BAR team were used primarily to carry extra ammunition for the BAR. They were named

Nelson (Assistant) and Hafer (Ammo carrier) Neither survived the war. I preferred to think it

was my leadership abilities and superb marksmanship that caused me this assignment. Actually

it was because I was the biggest and could carry all that weight.

Training in a division is different from basic. We did much of the same things but would

do it as a unit. 30 mile marches were very common and we had at least one a week. They

weren’t as hard as the shorter marches (10 miles) because these were mostly forced (A lot of

running).

On all these hikes, we were required to run the last half mile or so back to base. We spent much

time in weapons training, (assembly and disassembly, maintenance Etc.) And not near enough

time in actually firing practice. The Army was very stingy with ammunition.

Maneuvers were interesting. We would do simulated combat with blank ammunition and

sometimes with live ammunition. On one occasion we maneuvered with tanks. They had us lay

down in front of the tanks while the tanks were firing to get us familiar with the noise. This was

one of the worst experiences. The blast was deafening and the shock would make you bounce off

the ground. We also did advances under live artillery fire. On one occasion there were two short

rounds which fell pretty close to us. I had flopped down in this stubble field and a stalk jabbed

me under the chin. The cut bled profusely (I still have the scar) A Lt. ran up to me thinking I was

wounded by the shell. He was very ticked off at me when he discovered I wasn’t.

On maneuvers at Lake Murray in Oklahoma, I had a couple of adventures. One by nature

and one by my own stupidity. We were camping in the woods when a very violent thunderstorm

hit us. Lightning split and knocked down a large tree right by our (Nelson & me) pup tent. The

tree fell on the front of the tent but missed us. I decided then that I was probably indestructible.

During a break I decided that I could probably swim across the adjacent neck of the lake to a

tower of some kind. I wanted to see what it was. I had no bathing suit so I went in my birthday

suit. I tied my dog tags around my neck so they could identify the body. (I wasn’t too sure I

could swim that far.) By the time I got to the far bank, I was totally exhausted and wished I had

better sense than to do that. Just then I heard all these giggly girls laughing and I realized I

wasn’t alone. There was a girl scout troop camped near there. Knowing I was going to drown, I

got back in the water and swam for the far shore. It wasn’t easy but I made it.

On the 4th of July, our battalion was selected to march in a parade in downtown Dallas.

We set up our tents at the fair grounds. People walking down the sidewalk would bend down

and admire us trying to sleep. The parade was fun and I felt very heroic, since everybody clapped

for me as I went by.

Expert Infantry Badge

On one occasion my parents visited me at Camp Howze. It had become second nature for

me to use the only adjective used in the army. That adjective is f---ing.

As I drove them through the f---ing gate, through the f---ing intersection, to the f---ing barracks, I

suddenly realized it was very quiet in the car. Nothing was said about it but I am sure much was

thought. The army was not a good influence on their baby.

Our division got the basic elements of glider training just before we shipped overseas.

This consisted of loading and unloading out of mockups of the gliders. They even had that

stupid exercise of jumping off of platforms again. (I hate that) A few of us got to actually go up

in a glider. My squad was chosen. We sat on the ground with a nylon cable attached to us and

suspended between two tall poles. The C-47 flew over and snagged the cable, pulling us into the

air. It wasn’t as big a jolt as you might think; it was like being on the end of a rubber band.

After a very short “glide” we landed back on the ground. This glider had wheels as well as skids.

Most of them only used skids. Other squads were towed off the ground by the plane.

The short ride did nothing to make us want to repeat the experience. On banks, the fuselage

would noticeably sag and the wings would protest. The structure of wood and canvas seemed

very flimsy. There was a rumor going around that they were going to tow the entire division

overseas in these things. We all prayed it wasn’t true.

The squad leader was a man by the name of Newis. I didn’t like him very much as he

was very aloof. He got married just before we shipped out. I ran into him and his new bride at a

movie in Gainesville. She was extremely beautiful and nice. I can still see her in my minds eye

and wonder how she bore up at the news of his death. Newis was to meet a violent end while he

and I were lying side by side in a fire fight. I always felt his death was partly my fault.

Explanation later.

The entire 103rd division had a review just before we shipped out. Flags, bands, generals

& everything else all lined up and paraded. An infantry division has about 15000 men in it. It was

very stirring. The officer’s wives were lined up along the street and most were crying. The

enlisted men’s wives were not allowed on the base for this.

In late Sept. 1944, we took troop trains and headed east. This was the first indication we

were going to Europe instead of to the Pacific. We arrived at Camp Shanks New York near the

city. There we had some training, mostly climbing down nets off of simulated ships, loading

landing craft etc., and physical exercise.

I got two passes while there to go into New York. I tried to see the show “Oklahoma” but was

told it was sold out into the foreseeable future. The famous Stage Door Canteen was nearby and

I did go into it and met the “Girl who falls down” from that play. The significance of that part

now escapes me but it was a big deal at the time. I went up the Empire State building and some

other tourist attractions in the short time I had.

We loaded all our belongings into duffel bags (45 pounds), a full field pack (15 pounds)

and our weapons & kit (25 pounds) and by slow painful stages proceeded to the ships. I don’t

now remember the details but it was one of the more unpleasant happenings.

OVERSEAS The cruise

The ship I was assigned to was designed and built as a troop ship. This was a definite

improvement over the converted ocean liner. We did not share a bunk and did not have to take

turns going on deck. The meals were at predictable times and were always good. In fact, the

meals were among the best I had while in the Army.

HOWEVER

My bunk was on the lowest deck and was the most forward part of the ship. The ship was

so narrow at the front of the compartment that there was only room for one bunk. Mine.

We had a very stormy crossing and the movement at my bunk was unbelievable. When the bow

would rise to its highest point, it would shake VIOLENTLY and then plunge down and down to

its lowest point and then SWERVE back and forth several times. It was more thrilling than a

roller coaster but not much fun. Consequently, I spent most of the trip hiding on deck underneath

the life rafts. I escaped K.P. and other like details doing that. We did not have roll calls that I

can remember.

The convoy we were in seemed very large to me. It included a baby aircraft carrier and

quite a few destroyers and escorts. We had blimps escort us out of New York. The aircraft

carrier was damaged by the high waves on the Atlantic part of the trip. The flight deck was bent

up at a 45-degree angle and the planes were useless. We had no submarine trouble as far as I

know. We did pass two burning ships but the captain said it was due to a collision during the

storm. We passed through the Strait of Gibraltar just at dusk and went to Oran in north Africa

but did not get off or stay long. We had another violent storm in the Mediterranean. It was so

severe that all the life rafts and boats were washed off the exposed decks. The sailors said it was

the worst they had seen. I slept through the whole thing. After 14 days from New York, we

arrived off of Marseille in the south of France. We loaded into landing craft and charged ashore

with no opposition. The war had moved to the north.

FRANCE: Marseille and the trip to the front.

We carried the 45# duffel bag, the full field pack, and our weapons down a landing net

dangling above a landing craft at Marseille. This was a bit scary but very few were hurt. We

then began to march carrying all this stuff through the city and up a tall cliff to our staging area.

This took from about 10am to about 11pm that night. All of it was up a steep slope. It was very

difficult. After dark, a German plane flew over and dropped a flare. We understood that it did

that every night. Nobody shot at it. One of the weapons platoon men who drove a jeep with a

radio in it said that Axis Sally welcomed us to France. We were thrilled. (In a recent publication

of biographies of members of the division, the event often mentioned as the worst experience of

the war was this climb up from the docks at Marseille.)

The division encamped in a very large mudhole north of Marseille. Living conditions

were pitiful in the pup tents. It rained so much we couldn’t keep the mud from flowing into the

tent. This turned out to be good training for what was to come. We had no lighting at night, so

on my only pass into town I attempted to buy a candle. The French people I talked to thought I

wanted to pray and would direct me to a church. There were two long, long lines of GIs snaking

through town. One line was to the Cat house and the other line was to the pro station. (Or so they

told me) Black market people were everywhere wanting American currency. Those GIs in the

know who had any money easily tripled their funds in the blink of an eye.

I was assigned to a work detail, unloading supplies from ships at the Marseille docks.

There were mountains of supplies all over the area piled 20 feet high. I was working on

restacking a huge pile of Life Saver Mints which had been damaged. Those mints lasted me

quite a while.

There was a French civilian sitting up against a mountain of Anti-Freeze and was drinking one of

the cans. This is of course poison. Nobody stopped him. The Germans had scuttled most of the

ships in the harbor and about all you could see were the rusted bottoms. One narrow lane had

been cleared through the entrance. The ship I worked on was an English merchant. It was filthy.

It did not seem to have permanent bunks for the crew. They slept in hammocks which they

would take down during the day.

In late October, we loaded into trucks and began the trip to the combat area. Before

getting on the trucks they had us put our duffle bags in a huge pile. These had all our personal

possessions and anything else of value we couldn’t carry in our pockets. They said we would get

them back. We never saw them again. Because I was the BAR man, I was assigned to stand up

in the front of the cargo area with the tarp pulled back. I was supposed to be the air lookout and

defense. Never mind that the Army had given us no ammunition. I didn’t mind this as I got to

see the countryside. Sitting under a closed tarp, the rest of the troops saw nothing but each other.

It did rain or drizzle constantly. This was not a plus. About 50 miles north of Marseille while

going up the Rhone valley, we passed a destroyed German convoy of trucks, tanks etc. that

stretched at least 35 miles, bumper to bumper. They had been trapped by the French

Underground, we were told, and destroyed by the Air Corps. I was surprised the Germans had

anything left. Another interesting thing I saw was our truck crashing into a fountain in Lyon. All

the troops in the truck were thrown forward and crashed into me. I understand that is a very

famous fountain.

We arrived two days later near Epinal in Alsace. In the middle of a dark rainy night we

unloaded, attempted to get organized and marched to a staging area somewhere near there. At

about dawn we set up camp in another mudhole and began to get organized. We were issued

ammunition. I loaded all my clips with every fifth round being a tracer. My thumb was bloody

after all this. I was then told to take out all the tracer bullets as that was sure death to call

attention to your position. My thumb was in such bad shape that Nelson and Hafer did that for

me.

On Nov. 11, 1944, with a sleeping bag in our pack, ½ of a pup tent, a shovel or pick, water

canteen, spoon and raincoat we began our march to combat. The riflemen carried bayonets. I

was issued a knife with a 6-inch blade. Standard issue. It was dull and I had no way to sharpen

it. We all had one day issue of K-Rations. I liked K-Rations but nobody else did.

COMBAT

Combat Infantry Badge

My memory of the days in the combat area is hazy with a few glaring exceptions. I have

no doubt that I have confused the sequence of events. I will try to stick to the facts as I remember

them and not make myself look more competent than I was I will NOT mention my more

cowardly activities unless it is interesting. I will avoid when possible the gruesome details of the

result of infantry fighting.

The thing that first comes to my mind when I think of those days is the overwhelming

physical exhaustion. The constant movement, the lack of sleep, the difficult mountain terrain,

the cold, rainy and snowy weather made fatalistic zombies of us all.

The 103rd Division was assigned to the VI Corps which was part of the Seventh Army

commanded by General Alexander Patch. It was the Seventh Army’s job to penetrate the Vosges

mountains and hopefully cut off or destroy a large part of the German Army. The following are a

few published quotations from a recently written History of this campaign by a current Infantry

officer and a graduate of West Point. The name of this book is “When the Odds Were Even.”

It is the only campaign in Europe where neither side was able to use its air force nor tanks in any

meaningful way and the number of troops on each side was essentially the same.

“Remarkably, Seventh Army’s victory marks the first time in military history that an

attacker, by force of arms, had vanquished a defender entrenched in the Vosges.The GIs

were able to defeat his vaunted Wehrmacht opponent without the aid of fighter-bombers

and massed armored formations. Despite terrible climatic conditions and on terrain that

clearly favored a numerically superior defender, the GIs ousted Hitler’s legions from their

Vosges bastions “When the Odds Were Even.”

On December 1, after 14 days of backbreaking marches and sharp fighting in mountainous

terrain, thick woods, and winding trails, the 103d Division had broken through the Vosges

Mountains, a new “first” in military history and a feat which the enemy had considered

impossible.

We began our adventure with long columns walking up the road into the Vosges

mountains. My group was not in front of this column. The leading elements were often fired

upon by the Germans who would then disappear while the GIs dispersed into fighting groups to

look for them. This was of course a delaying tactic.

We relieved elements of the Third and 45th Infantry Divisions. They were part of the VI

Corps and had been moved up from Italy along with the 36th Division and the Japanese

American combat team The Japanese team suffered 80% casualties in the next two weeks. We

didn’t do much better.

They were a sorry looking bunch and seemed thoroughly whipped. They kept telling us to quit

bunching up and other good advice which we thought was unnecessary to fine soldiers like us.

Later, we became just like them. They had fought the preliminary battles of the campaign and

had captured most of the highest ridges. Their moral was very low. They had been fighting

defensive battles from prepared positions. In one of these holes (It even had a roof of logs) I

found a part of a “Frederick Leader,” my hometown newspaper. I was never able to determine

that anybody from Frederick was in that area and wondered if it might have been meant for me. I

never got any mail while I was overseas.

We did send out patrols to our flank and front. This was usually late in the day before we

stopped for the night. I was INVARIABLY picked to lead the patrol (Because I had the

firepower, BAR). This resulted in my having to dig a foxhole after dark when everybody else had

sacked out. I never was able to finish a fox hole while I was in combat. Very often, we

“captured” a town or farmhouse and managed to sleep indoors. The squad took turns being

lookouts or outposts at night. I was not excused from this. We had some casualties (In the

Company) every day. Early on this was from Booby traps, mines and occasional artillery fire.

The villages we passed through often had booby traps behind the doors of the houses. We all

hated checking the houses for Germans for that reason. Sometimes, we didn’t check them and

said we did. We figured if there were enemies in them, they would have shot at us before then.

Another favorite trick of theirs was laying a hand grenade in the middle of the road as though it

had been dropped. Picking it up or moving it was not the thing to do. I personally never

witnessed any casualties from these things but we were told they were common.

The first time I fired my BAR at anybody was a surprise to all concerned. It was early on

in our advance and we were advancing through woods in combat formation as we had heard

firing in the area. We were not the point group. As I stepped out of the woods onto a narrow dirt

road, I saw one of our squad raise his rifle and fire down the road. I looked that way and saw

what turned out to be a German staff car coming our way. As more of a reflex than a deliberate

action I emptied most of the 20 round clip into the car. One door opened as the car ran into a

ditch and one man fell out. There were three German officers and a civilian in the car. All were

dead. We didn’t hang around to find more about this or their intent. Later a Lt. whom I had not

seen before approached me about the incident. He seemed to think I had leaped into the road to

do battle and mentioned a possible citation for me. I did nothing to discourage him. Nothing

ever came of it. I was surprised at my reaction to this first shooting: I had no reaction. I think

this was typical of most of us.

We lost two squad members on the second day. One was called back to the states for

Officer training (They forgot about me again) and another was sent back because he couldn’t take

the physical strain. He was the old man of the squad; he was 25. The rest of us were teenagers.

We got one replacement. His name was Prianti and he was from Brooklyn. I felt sorry for him

as he knew no one. I felt he would be the first to die. He was.

The most physically demanding episode I have ever endured happened a day or two

before Thanksgiving. We climbed this mountain in the dead of night in the usual drizzling cold

rain. It was totally black and you could not see the proverbial hand in front of your face. We

were going in double file up a road so steep and muddy it was difficult to stand. Some Jeeps

with shielded lights were also on the road. I was so exhausted that I fell over backwards and

couldn’t get up. A Jeep was coming and the only way I could keep from being run over was to

roll off the road. The mountain was so steep at that point that I rolled quite a distance before I

could stop. I could not climb back up so I worked my way laterally back to the road. By then my

group was nowhere to be found. I rejoined them about dawn.

We dug in on top of this mountain and awaited orders. While trying to dig my foxhole I

kept running into all this wire on the ground which impeded my activities. I was ticked off at

whoever left it lying around so I stupidly cut it and moved it. It turned out I had cut the

communication lines from us to Company Headquarters. They soon came by and repaired it. I

looked as innocent as I could. That night we got the only hot meal of the campaign. It was

because of Thanksgiving they made the effort. I don’t know how they got that kitchen up the

mountain. None of us had anything to put it in but our canteen cups as our mess kits were in the

duffle bags in Marseille. Salad on bottom, main course in the middle and desert on top. We

tried to eat this glop with our spoon in a driving rainstorm on the side of a steep muddy mountain

in very heavy brush. It made nearly everybody sick, including me. I smoked my first cigar

instead. My first ever. I forget where I got it.

The next morning, I awoke in my foxhole feeling warm and cozy. I was covered by an

8inch blanket---of SNOW. We were snowed on occasionally, but not like this. The sun came

out and it was beautiful. Everything seemed right with the world. That mood didn’t last long.

That night Nelson and I were on outpost on the flank of the mountain overlooking the

town of LaBolle which is near St. Die, our objective. The snow had melted and the foxhole was

full of water and mud. In the infantry, you can sleep anywhere and we took turns doing that.

S.O.P.. While I was on watch, something happened that scared the daylights out of me. I heard

this loud crashing through the brush and it was getting closer. I had no idea what it was and was

considering shooting in that direction. It turned out to be a bunch of horses. They ran by about

20 yards from us. I don’t know what spooked them or where they came from. The Germans

used a lot of horses in their transport. I felt very silly being so scared. Usually, you are too tired

to be scared. The next morning, we were relieved by other members of the squad and we started

back to rejoin the company. We sat down on a log to rest next to a couple of soldiers who

seemed to be sleeping. They were dead. We couldn’t tell what happened. Very depressing.

Coming down from the mountain we encountered the Meurthe River. It flows in front of

St. Die and had to be crossed to get to St. Die. Here occurred one of my many cowardly acts.

That night, me and my squad (Nelson & Hafer) were ordered to cross the river and scout the

other side for 300 yards. We were to listen for enemy activity and capture one if we could. This

was being done by other groups up and down the river. As usual it was pitch black and raining

lightly. We got our rubber raft to the other side without incident but could not bring ourselves to

go further. It seemed suicidal as we could hear Germans. We did not want to capture one. We

reported the activity to the Captain. (The only time I saw him in the combat area) He said that

confirmed what he suspected. We were to expect a contested crossing. The engineers built a

pontoon bridge about a mile away and we crossed there with no opposition the next day. We then

proceeded down a road to the area where we had heard the Germans. The road was adjacent to

the river and a very steep brushy slope was adjacent to the road. The Germans had a line of

trenches about 30 ft up the bank from the road. They could not be seen. Our idiot Lt. ordered

“Fix Bayonets” and told us to climb that bank. It was impossible. We then found an easier way

to get up there and it was obvious the Germans had departed. This fortification was well made

and had been there some time. It looked like a WWI trench with small rooms cut into the side.

We then proceeded down the trench to make sure it was clear. As we rounded a turn, a German

soldier carrying their equivalent of a Bazooka stepped out of one of the side rooms. He seemed

no threat and as I was about to ask for his surrender, my ear was nearly shot off by Nelson who

was shooting the German. This made me mad as it was unnecessary. Nelson thought he had

won the war and was a changed man after that. He became a real killer. Later in St. Die, while it

was burning at night, an old civilian man ran into the street and Nelson tried to shoot him. He

missed, but I had to physically restrain him. From then on, he was the first to fire at anything.

Sometimes that was good.

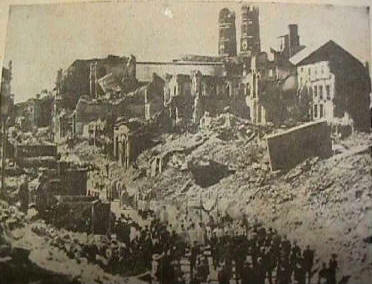

We captured St.Die as it was burning. The Germans had set it on fire for reasons known

only to them. It was virtually destroyed. The division then passed further into the High Vosges

where we began to run into serious opposition. Most of the activity is confusing in my mind.

St. Die was a charred ruin when the 103rd arrived

American Memorial Building. St. Die.

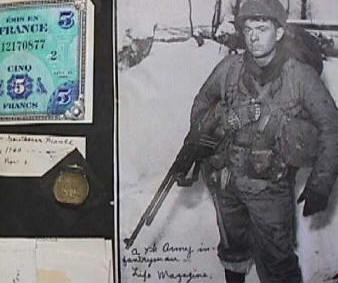

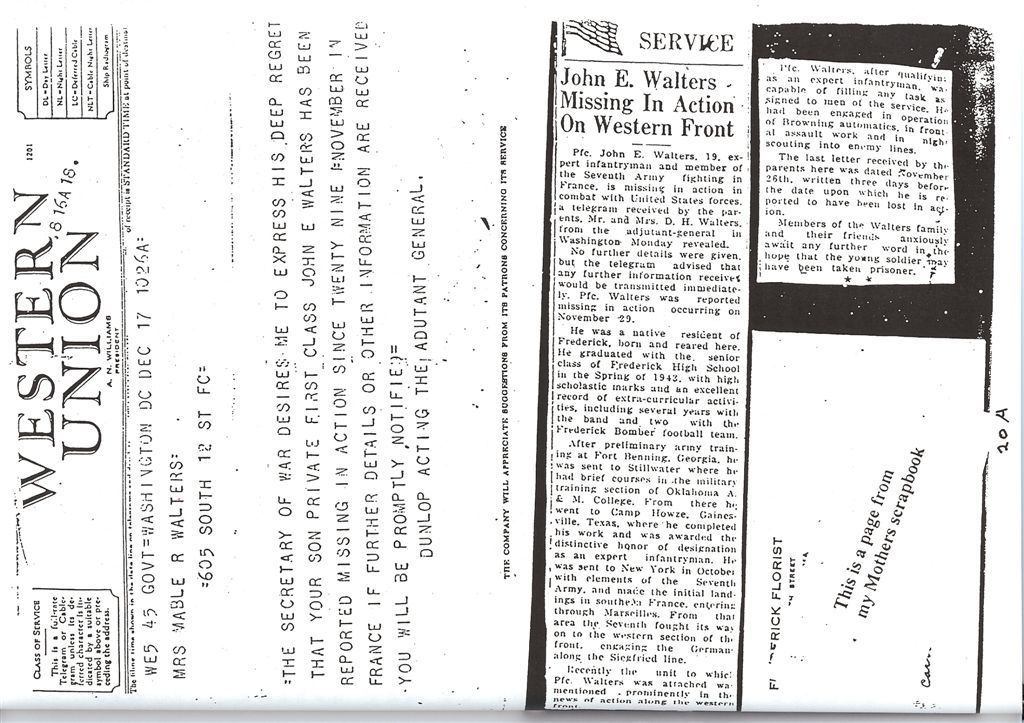

This is part of a page from my Mothers Scrapbook she kept for

Me during the war. She did this for all the kids. The picture

Is of a BAR man in the mountains. This is the way we dressed.

The BAR has the bipod removed. I did that also as it was always

Hanging on the brush. Sometimes, I wished I still had it.

Some Episodes I Remember:

A muddy plowed field east of St. Die

While crossing a very muddy plowed field in the rain, a German artillery shell hit

amongst us and tumbled end over end and stopped about 10 yards from me. It seemed to be

moving in slow motion but of course wasn’t. I took this as another sign that I was indestructible.

In this same field, we passed a German multi-barreled antiaircraft gun mounted on a wooden

cart. How or why it was there we didn’t know.

The town of Ville: A bitter fight and many casualties but not to my squad. We took over what

must have been a children’s hospital in the early afternoon. (All the beds were short) It was

deserted. It had an earthen berm all the way around it about 10 feet tall. The only land

overlooking the grounds was some distance away. I was bored and went out into the space

between the building and the berm and began playing with a stick, throwing it into the dirt as

though it was a spear. I fear I may have attracted attention doing that. I tired of that and went

back into the building just as Prianti and another of the squad came out and began to play with

the same spear.

The Germans dropped a mortar round right on them. Both were killed, Prianti not instantly. His

stomach was ripped open and he kept trying to raise up even after the medics said he was dead.

This upset me as I thought he was still alive. The squad was now down to nine.

A rough and tough truck driver:

Rear echelon troops always seemed to strut around and act tough. This guy had pulled

over beside the road to let about 15 German captives pass. We were sitting beside the road

resting. This jerk jumps out of his truck and fires his little carbine into the prisoners. He hit one

in the foot. He said he hated Germans and would kill them all. It was the first time he had been

anywhere near the action. He was very proud of himself. An officer had to restrain several of

our company from beating him up. The officer said he would be disciplined. I saw the same

attitude when I began to penetrate the rear of the German army after my capture. The safer they

were, the meaner they were.

A Roadblock in an unremembered village:

Our squad took over a house, one wall of which adjoined a German roadblock.

This was not a smart move on our part as roadblocks are usually defended. The house was well

built with old thick walls. That was fortunate as they scored a direct hit on it with something big.

We were eating K-Rations at the kitchen table. Two of the guys had

minor glass cuts but I didn’t. I was still indestructible. I found a French

medal in a drawer there. (We “liberated” only small things we could

carry) and what I thought was a miniature gold spoon. I am not sure of

the rank of this medal but I think it is one of their highest. It is the

Medal Militaire. I kept it through the war and still have it. When

questioned by the Germans about it I told them it was a souvenir. They

let me keep it.

That night while on guard duty, foolishly using a German Burp gun, a

civilian came up to me in the dark and wanted to talk. He kept trying to

give me wine which I refused. He didn’t know that I would have shot

him if I had my own weapon. I was afraid shooting off that very

distinctive burp gun would have started something unpleasant. The

miniature gold spoon turned out to be a gilded standard teaspoon. I was

so used to seeing the Army spoon that I didn’t recognize it for what it was.

A mountain top in the High Vosges

While lying among trees looking across a deep valley at another mountain which

supposedly held the enemy, a fighter plane appeared out of the mist behind us and began firing. I

thought it was an American plane firing at the Germans. Others thought it was firing at us. I

found an ejected cartridge which thunked the ground near me which looked like the 50 cal. round

used in American fighters. That was the only plane we saw while in combat. The book about the

campaign said the Germans had captured an American plane and used it against our troops. This

might have been it.

A nice French lady’s house:

We spent one night at a house where the occupant was still there. This was rare. The

lady made up a bed for me with clean sheets. We never took off our clothes at night but I made

an exception and took off my muddy boots. I was having trouble with nose bleeding at the time

and during the night I bled all over me and the bed. She spotted this and decided I was wounded

and raised a big fuss. Very embarrassing.

A French barnyard

I learned the hard way what the tall piles of what appeared to be hay stacked up around barnyards

actually was. While moving through a farm in the dark, I leaned up against a pile of hay only to

discover it was a pile of manure with thin layers of hay between. I smelled worse than usual for

two days. I had very few friends for a while. The manure was very fresh.

Somewhere near St. Die:

We were preparing to cross open ground from one small village to another. The village ahead of

us was being shelled by artillery using phosphorus rounds. These burst into the air with

spectacular trails of white flame. As several halftracks and other vehicles raced across the 1/4

mile opening, they were fired upon by a German gun, probably an antitank gun. Every time one

made it across successfully; everybody cheered. None were hit. When it became our time to

cross, I feared the worst. We weren’t very swift on our feet. I was lying up against the wall of a

house thinking that this was not a good way to make a living. I rolled over on my back to look

around and spotted a mother and her two children looking at me out of the window directly

above my head. They smiled at me as though this happened every day. I attempted to look stern

and fierce. I wish I had smiled back.

MY FINAL BATTLE

On November 27 or 28 we began moving rapidly down out of the mountains into the

valley of the Rhine River. We were nowhere near the river but it was obvious we were coming

down out of the higher mountains. The weather had improved, the road was PAVED, which was

rare and there was no sniper fire or other activity of that type. I wondered if the war was over.

That afternoon it became obvious it wasn’t. As we neared the town of Itterswiller, one of the

leading elements spotted a German tank, the first we had seen. This was not good news as we

had no tanks. Our squad could not see it but one of the weapons platoon men came up with a

bazooka and climbed a high bank near the road and fired it at the tank. He later said it was

probably too far away to hit anyway. He missed it. This brought a barrage of mortar fire down

on our heads. Fortunately, it was probably their smallest mortar. Unfortunately, we were on an

extremely flat stretch of ground which had no place for cover. This was my most frightening

experience of the war. Lying fully exposed on the flat surface, the rattling and whirring sound of

the shrapnel passing over my head made me think of all the bad things that could happen, such as

missing parts.

I tried to put my entire body under my helmet. I may have succeeded as I wasn’t touched and

neither was anybody else in the squad. Others were not so fortunate.

That night, we dug in on an open field into obviously defensive positions and were told to

expect an attack. There was occasional machine gun fire and artillery fire but not at our position.

On one occasion, tracers from a machine gun were deflected up into the air. We assumed it was

firing at a tank. Flares were set off constantly, but I never saw anybody. Nobody got any sleep.

The Germans were using their “Screaming Mimi” mortars. They have whistles on them and

make this unearthly wailing noise while they are in the air.

Early the next morning, the firing had stopped, the weather was trying to clear and I

assumed wrongly that this had been another delaying tactic. As we got out of our exposed

foxholes, nobody fired at us. The sergeant explained where our assigned advance would be. It

was rare that anybody explained anything to privates. Our first objective was to be the town of

Itterswiller.

Itterswiller was at the terminus of two plunging ridges. A paved highway went down

between the ridges, made a right turn at an intersection with another road and went about ½ mile

into the town. Our company (B Co.) was assigned the ridge on the right or south side. The ridge

was very heavily wooded and had an untended grape vineyard on the lower slope. (This is an

important wine growing area) There was a narrow dirt road that rose from the paved highway to

near the crest of the plunging ridge as it neared Itterswiller. My squad was assigned the point

position. We forded a small stream and climbed past the dirt road and climbed up to the crest of

the ridge. The brush was so thick, it was impossible to see more than a few feet but by lying

down and looking under the brush, visibility was probably 50 yards. At a prearranged time we

began descending the axis of the ridge, while other elements of the Division advanced down the

highway in plain view. Another Company, (C Co.) was moving down the other ridge. We had

not moved very far when we heard firing by a German machine gun directly below where we

were. Our squad scout crawled in that direction and soon called us that way. The machine gun

nest was dug into the edge of the grape vineyard in plain view of us who were above them. The

squad leader then called me and my team into position and we easily disposed of them. There

were two of them and they never knew what hit them. They were firing at the troops moving up

the valley. (C Co.) We could now hear a lot of firing by other Germans directly ahead and below

us. Following the same procedure as before, we surprised another position and got them before

they knew we were there. This was so easy that it was difficult for the squad leader to maintain

fire discipline. Everybody wanted to get into the act. So far, I had done most of the shooting.

This would lead to Sgt. Newis being killed.

The next German position was different. The scout spotted a single German much

higher on the ridge and almost directly in front of us. He could only be seen by lying on the

ground and looking under the brush. I could only see his head. I fired and got him. He was in a

very narrow and deep hole he could stand up in. He was armed only with a rifle and I suspect he

may have been some sort of rear guard to protect against just what happened. He may have been

a sniper. He was one of the few enemy casualties I had the opportunity to see up close. He was

extremely young and to this day I wonder if it wasn’t a girl. The thought occurred to me at the

time but I could think of no way to find out that I was willing to try. The body was still standing

and I felt very bad about it.

By this time we had come to the little dirt road and we began crawling up it as we could

hear more machine guns below it. It offered good cover from the guns below us. In the

meantime, the troops coming up the valley were being shot up by the remaining machine guns

and artillery fire. They were taking cover in the small creek which flowed beside the road. At

about this time, a German tank appeared at the intersection and began firing down the valley.

We continued to move up the little road. Sgt. Newis crawled up ahead and looked over the edge

of the road. He then raised up into a kneeling position and began firing his rifle. This was not

according to his procedure, as he should have called for the BAR team if he spotted something.

He then flopped down and began frantically waving at me to join him. I knew we were in trouble

from the expression on his face. I crawled up to him and asked him where the gun was. He

pointed over the edge and said “THERE, THERE, THERE.”. I saw a gun position about 200

yards away and thought that was it. I began to fire at it but he banged me on the shoulder and

said “No No There” I then saw the proper position only about 40 yards away. There were two

men in it and the bigger one was in the act of picking up the machine gun, slamming it into the

ground and pointing it at us. He was so close I could see the expression in his eyes. We made

eye contact. The other seemed smaller and was bent over in their hole. He may have been hit by

Newis. I had a bead on him and fired the BAR. I had only four rounds left in that magazine. As

I rolled over to get another clip, he fired. If I had not been in the act of rolling over to my right to

get another clip, that first round would have got me between the eyes. The first round grazed my

cheek just below my glasses. It felt and sounded like a firecracker exploding in my face. It

caused a line of bloody blisters. His following shots walked to the right and disintegrated Sgt.

Newis. Bones came out of his back and he was making this horrible sound. I was drenched by

his blood.

I then fired at the position again and I know I hit the gunner as firing ceased from his direction

but I could not see him anymore. I slid back into the road to reload where I couldn’t be hit from

below when he started firing again. There was a constant fire at the edge of the road which never

seemed to stop. It was a belt fed machine gun and he apparently had lots of ammunition. He was

keeping our heads down.

About this time, an American tank destroyer appeared at our position and wanted to know where

the German tank was. We told him but the tank was nowhere to be seen. The tank destroyer

looks formidable but has very thin armor. The machine gun had stopped firing and everything

seemed better. The tank suddenly appeared and began firing at us. The tank destroyer then

backed up and left. I don’t know why; he never fired a shot. The machine gun began firing

again.

We couldn’t move forward because we would be exposed to the machine gun. The squad Sgt.

ordered me to crawl down a line of brush toward the grape vineyard and see if I couldn’t get him.

It is not easy to crawl with a BAR ammunition belt so I took that off as well as my pack and

began to SLOWLY crawl down the slope. My heart wasn’t in it and after about five minutes

when I had progressed about 10 feet, the Sgt. told me to come back. About this time was when

the Germans decided we were a major threat and begin to unload on us with everything they had.

I am sure most of it was mortar fire, but the tank was definitely adding his gun to it. I thought at

one time that some of the shells were American but I am not sure. The firing was so intense the

very woods all around us were beginning to disappear. At least two of the squad were hit but not

seriously. The machine gun had stopped again and the Sgt. said “Lets Move Out.” I was still

trying to retrieve my belt and pack so I was the last to leave. HOWEVER, I was apparently

knocked unconscious by a near miss. I woke up later lying on my back, beside what had been a

tree with an 8-inch trunk which was only a stump. My head was

against that tree. A wood splinter about the size of a tent stake was

sticking out of my leg. This looked awful and bled profusely but was

actually superficial and gave me little trouble. I was covered with

blood, mostly from the Sgt. but a lot came from my nose which was

still bleeding and from my leg. At the time, I didn’t realize I had been

unconscious but was surprised to see that it was late afternoon and

nobody was shooting. (Time flies when you’re having fun) I got my

belt and pack and began to run in a crouch toward Itterswiller to catch

up with my squad. The area for about 100 yards had been completely

stripped of vegetation by all the shelling. It looked like a World War I

battlefield. The trees and vegetation began to thin out and I could see a

deep valley between me and Itterswiller. I could see no sign of the

squad as the terrain in front of me was open. I could see into

Itterswiller and could see Germans. I then decided I didn’t know what I

was doing and began a cautious retreat, wondering where everybody

was. There was no sign that the army had been there. I suspect but

don’t know that the squad probably pulled back instead of going forward. As I got back to near

where I was earlier, I began to hear a voice from the German gun we had so much trouble with.

It was the voice of a boy. He was crying Kammerad (Surrender) and was also crying for his

Mother. I considered shooting him but didn’t. I think maybe he was wounded and was the one

doing all the late firing. I am sure I got his partner.

About this time, I saw walking up from the way we had come what turned out to be an

officer Artillery Spotter. They normally will hide out in forward positions to direct artillery fire.

He wanted to know who I was and what I was doing there. I felt like a deserter. He said”Come

with me.” He took me back down the hill to where a group of dead and wounded were. He had a

jeep and driver there. He had me help one of the wounded into the jeep and we drove back down

the road and across a field to what was the Battalion Command post. He ordered me to wait

there for some Medics, and to guide them up the mountain to help the large number of casualties.

I did not see any of my squad among the casualties but most of the bodies were lying face down.

My BAR was lying in the jeep and as the Lt. began to drive away I hollered at him to get it back.

He ignored me. (To give him the benefit of the doubt, he may have thought I was hurt worse than

I was and wouldn’t need the gun. He may have meant the medics for me.) I suspect he really

wanted that B.A.R. I was then unarmed and felt naked. This probably saved my life. I would

have felt obligated to use it when in danger of being captured.

NOTE

My mother had written to various soldiers I had kept addresses on. One, a man

named Reeder, was a member of another company. I knew him at Okla. A&M. He came over

to B Co. And inquired as to what happened to me. (This was some time later, after I was

reported missing in action) He was told that I had gone out in front of the lines to rescue

somebody and did not return.

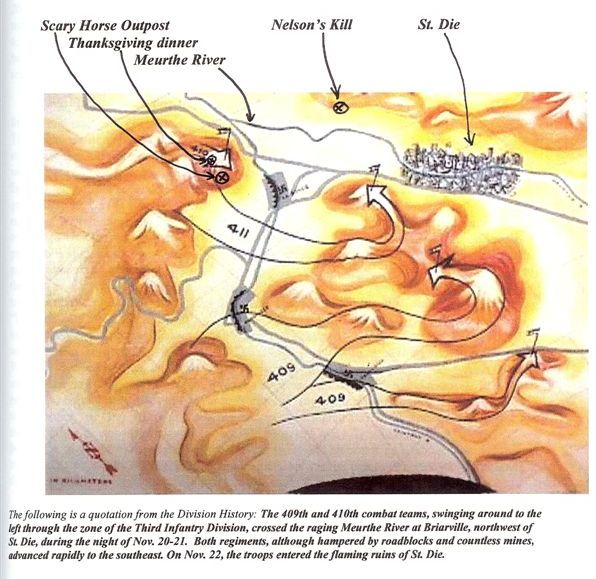

This battle and this Lt. was mentioned in the Division History. The following quotations

are from that book.

During a series of small actions near Itterswiller, “B” company of the 410th Infantry

Regiment was subjected to intense mortar and small arms fire. The company suffered

heavy casualties, including all its officers. A red-haired, freckle-faced artillery officer came

to the assistance of the company and reorganized it. After that long, cold night of

November 29, “B” company was only a thin line of its former strength. Second Lieutenant

Clare J. Boyle of Ogden, Utah, was a forward observer whose communications with the

383rd Field Artillery battalion had been cut by German shells. The lieutenant gathered the

riflemen the next morning and successfully led them in a drive on Itterswiller behind the

protection of a rolling artillery barrage. For that action Lieutenant Boyle won the

Distinguished Service Cross.

NOTE

It seemed to me that officers got most of the medals. The privates didn’t last that long.

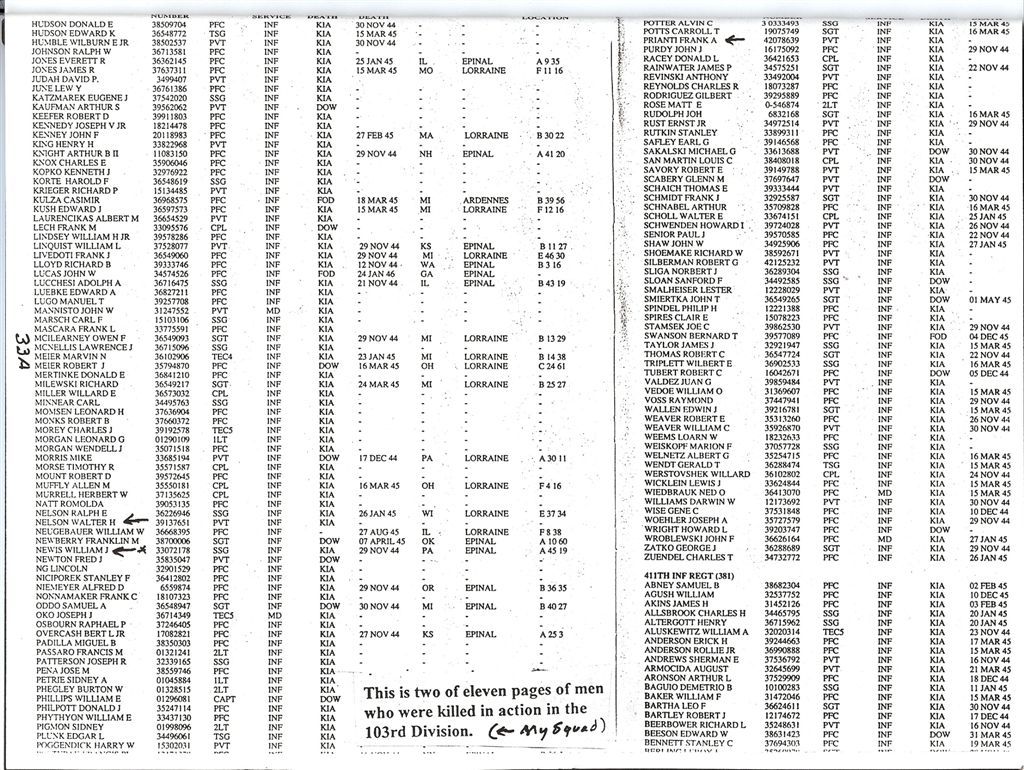

After I got back to the states, I tried to write to other members of my squad. All but Hafer, my

ammunition bearer died that day. Hafer was killed March 15, 1945. I did not see them die. I did

get a letter from the platoon Sgt. (Promoted to First Lt.) He said only nine men were left in the

company at the end of the day. (The company was around 200 men at that time.) I don’t know

how many of the casualties were killed but there were at least 43. I could not bring myself to

reply to the requests for information from the parents. I am still ashamed of that. The award

given to Lt. Boyle that day was the highest award given to anyone in the division during the war.

One other man and the Commanding General (Gen. McAuliff of “Nuts” fame got that medal.)

Since I helped him on part of his mission and he stole my BAR for the rest, I think part of that

award belongs to me. Ha

Another Note

Tony Hillerman and Huckins were in the first patrol to enter Itterswiller the next day.

Huckins shot one German.

Back to the story

There was a small garage attached to the house and I lay in it behind some lumber. I felt I

was so far behind the lines that I was probably safe. I was shaking so violently I almost bounced

off the ground. I don’t know if it was the cold or was the relief from the adrenalin. I was

miserable but safe (I thought; this was Officer country). I knew I would be in trouble for losing

my gun. I was very ticked off at the Lt. As it began to get dark, a high velocity shell penetrated

clear through the garage but didn’t explode in it. I was so exhausted and inept that this didn’t

even alarm me. I think I had some sort of shell shock. There was then quite a bit of shelling

going on and somebody came out of the main building and told me I could wait for the Medics in

the basement. The basement turned out to be a wine storage area with huge wooden barrels. I

crawled beneath one and passed out. I don’t know whether I dreamed it or not but someone

MAY have called down and said they were pulling out. If that did happen, I ignored it.

Sometime around midnight, I was waked up by very loud explosions inside the house above me.

Shrapnel was coming through the floor and making sparks on the cement. The house above me

began to burn. I could hear a tank running outside that was obviously firing into the house. I was

now fully awake and was trying to decide whether to burn up or climb out and let them shoot me.

I then heard a voice in good English holler that anybody who wanted to surrender should come

out and do so. He said his name was Pennington. I did not hesitate long and climbed the ladder

to get out. There was another soldier I did not know down there with me. He was just as

surprised as I was. When I got up to ground level, there was this huge tank with the gun inside

the house (That wall had fallen away) and a group of German soldiers all pointing their rifles at

me. There was no one who admitted being Pennington in evidence. They were all German

soldiers. While they were searching me for weapons (They missed my knife) the 22 American

Medics I had been waiting for marched out of the darkness in good order. They had no idea what

was going on. I suspect that the large casualty count suffered by B Co. was partly because of the

lack of aid by the medics. The wounded probably froze to death during the very cold night.

They marched us in total darkness down the road toward Itterswiller. We passed quite a

few German troops and one more tank. About half way to the intersection we were challenged

by an American outpost who said “Halt, who goes there?” I was amazed and frightened by this

stupidity. He probably heard all the rubber soled boots Americans wear and didn’t know he was

outnumbered. Somebody (It may have been me) said “We are Americans.” There was a long

silent pause and the guards moved us on down the road. (In 1997, I met these two men who were

manning that outpost. The were manning a machine gun. I thanked them for not shooting me.)

As we got to the intersection and started toward the town, we came under American artillery fire.

One round landed amongst us. It was dark and difficult to see but as near as I could tell, two

were killed & several wounded. The heel of my boot was sheared off and the seat of my pants

was exposed. I was not hurt otherwise. Later, the Germans said they drove a captured jeep with

a couple of the wounded with stomach wounds to near the American lines and left them. I don’t

know if that was true. We were kept in a yard in Itterswiller for about an hour and then moved

into the second story of a place which seem to put on plays. There was a stage which we were

arranged upon. They gave us a can of meat to eat. It was nearly all grease or fat with a thin

column of meat down the middle. These troops were obviously mature and experienced soldiers

and treated us well. They wanted to know why we had surrendered. I suspect the young kids we

20

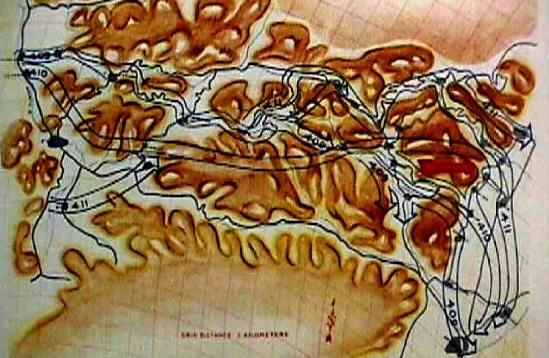

This map shows the terrain from St. Die to Selestat. The paths of the regiments is shown by

parallel lines with the name of the regiment written between the lines. I was in the 410th. The

path of the 410th went from St. Die through Ville where Prianti was killed, through Itterswiller,

near where I was captured and to Selestat, near where I spent the night of Nov. 30, 1944.

Quote from History: Heavy pressure exerted by the attackers forced a passage of the Vosges

Mountains when the 410th, outflanking the mountain pass from Provencheres to Fouchy, fought its way through the

minefields and mud to the town of Ville on November 25th.

St. Die Ville

Itterswiller

Captured here

Selestat

Quote: German defenses of the walled city of Selestat were cleverly conceived and well executed. Selestat, a city of

15,000, was situated like a pancake in a frying pan, rising up out of flat ground---a defending machine gunner’s

dream. Around the town, as an outer defensive ring, the enemy had deeply dug-in machine gun emplacements.

encountered in the fight were probably the Hitler youth that they committed in the late stages of

the war. I don’t really know. The next morning, we moved out to the South toward Selestat and

the beginning of my Prisoner of War stage.

PRISONER OF WAR Nov. 30, 1944 to May 3, 1945

It was dark when we arrived in Selestat. There were about 15 of us. They put us into a

box car and left us there for some time. We nearly froze to death, actually. I got severe frost bite

and had difficulty walking when the opportunity came. When we were let out, we began walking

to the east. We crossed the Rhine River on a raft pulled by cables. We then walked a few more

miles and were put on a civilian train. The passengers looked at us as though we were from outer

space. I was surprised the trains were operating. I thought they had all been destroyed by our air

force.

We were taken off the train in Freiberg and marched down the street to a school building

which had obviously been bombed. Workers were still digging children out of the debris. On

this short march we were pelted by a few rocks but our guards made them stop. The school was

next to the tracks which were not hit. I saw no evidence of other bomb damage. Very strange.

Next, we marched up onto the side of a hill overlooking the rail yard and sat there for

sometime. This was the Black Forest and seemed very sinister. It had now been about three days

since we had anything to eat and we were beginning to feel it.

At some point we were transported to a camp at Ludwigsburg north of Stuttgart. I can’t

remember now how we got there. This was a converted dairy. I don’t know if it was a regular

POW camp or not. I saw very few people, Germans or POWs. We spent several days there.

There were no bunks. You either slept on a wire frame that was meant to hold a mattress or on

the cement floor. While I was there, the Germans gave me a pair of shoes to replace my

damaged boot. They were apparently French Army issue. They replaced my torn pants and my

shredded and bloody field jacket with almost new American issue. I don’t know where they got

them. They did not have any stenciled name in them. They also gave me a French Army

overcoat. My knife was discovered at this point and my steel helmet was finally confiscated. I

am sure they must have fed us but I can’t remember.

A large group of prisoners was loaded into two boxcars and began what we were told was

a trip to permanent camps in the interior. We were loaded into a boxcar with so many people

that we could not all sit down at the same time. We were told this would be a short time because

we were to transfer to something else. They also said the camps where we were going were very

nice and that we would like them. None of this was true.

We had been allowed to keep our canteens filled with water. This was fortunate since

they didn’t let us out of that boxcar for about seven days. We got organized and managed to

arrange for times to sit down and rest. Several vicious fights broke out because of the crowded

conditions. Four men died on the trip. I don’t know for sure what happened but the fights may

have contributed to this. Since the call of nature had to be answered and there was no place to do

it, we had a problem. The four bodies were stacked up near one wall and people relieved

themselves on the other side. This train trip was the first period of intense starvation we were

This is a map of Germany and surrounding areas. The places indicated in color are some of the

places mentioned in this paper.

subjected to. Most of us had some scraps of food in our pockets so I doubt if any of the deaths

were because of starvation. I had a place to stand near a grilled window which let in air. We

spent at least three days in the rail yards at Ulm. (I saw a sign out the cracks) It was snowing

heavily outside and I was able to scrape off enough snow to put more water in my canteen.

Every time we stopped anywhere, we would pound on the walls, and demand to be let out.

Nothing happened and nobody acknowledged

The doors to the train were finally opened and we were let out at the town of Dachau. We

knew nothing of the infamous concentration camp there so were not alarmed. They said the trip

took so long because of air raids and that no guards had accompanied us. They seemed shocked

at our condition and at the presence of the dead. Dachau is near Munich but we were headed for

Stalag VII A near Mooseberg, northeast of Munich.

A strange thing happened to me and one other fellow while we were there. We were

transported several blocks to a small building outside a barbed wire stockade. We were

questioned for several minutes in only French. They were very interested in my French Medal but

let me keep it. We were both wearing French clothing and they probably thought we shouldn’t be

with the Americans. They then questioned us in English and took us back to the train. The

group we had been with was nowhere to be seen. We rode in a German troop compartment to

Mooseberg.

This seven days in that boxcar changed my personality I think. From that point on, I lived

completely inside myself. It seems as though I spent the rest of the war in total isolation. I

cannot clearly remember anybody as an individual. I made no friends -- or enemies.

STALAG VII A About the middle of December 1944

This camp was one of the largest in Germany. It had many prisoners from various nations and

services scattered over a large area. I could see very little of this as visibility was limited by

buildings and barbed wire fencing. The first place I was put (with the other “Frenchman”) was

not typical of what was to come. There were just the two of us in a small room with no bunks.

The fenced area was small and had its own latrine. They gave us a straw mat which turned out to

be crawling with man eating fleas. Their bite made sores the size of a dime. It was miserable.

We stayed there only two days and were sent to the more typical quarters.

The compound I was assigned to was typical of the entire camp I am told. There were

four buildings arranged in a rectangle and surrounded by a double barbed wire fence with coils of

wire between the fences. There is a trip wire about 6 feet from the fence with signs which stated

that anybody crossing that wire would be shot. They meant it. The barracks were about 100 feet

long and about 40 feet wide. The walls were lined with wooden platforms with shelves going to

the ceiling which served as bunks. They were stacked four high. I had the top bunk. I was glad

about this as it was usually warm near the ceiling. It would have been very bad if it had been

summer. There was a pot bellied stove near the middle of the barracks but we had no fuel for it.

We didn’t need it as the large number of men in tight quarters supplied sufficient heat. At one

end of the barracks was the quarters of the noncommissioned officer who was in charge of the

barracks. He was an English Sgt. We were all American privates. Prisoners are segregated by

rank. Only the privates were required to work.

My compound had two barracks with Americans and two barracks with Polish soldiers.

We had very little to do with each other. They seemed to exist better than we did. We were near

the edge of the camp. There was one compound between us and open country. The compound

next to the perimeter was for Russians. While I was in the camp, at least four of the Russians

were shot because of the trip wire. One time, we had two men wounded while in our barracks.

The bullets fired at the Russians came through the walls and injured them. We were told they

treated the Russians differently because the Russians did not recognize the Geneva Convention.

There was a large latrine with no running water. The place would occasionally fill up and run

over. It was as big a mess as you might imagine. The “Honey Wagon” usually came before that

happened. There were no facilities for washing. There was one outside faucet but we never got

any water from it as it was always frozen.

Camp Food

Breakfast: There was no breakfast. The guards normally brought in a barrel of hot Ersatz coffee

or tea. The “tea” was normally so bad that we usually used it to wash with. It was hot however.

Lunch: If we were in the camp at lunch time (This was rare as we usually were out working

somewhere during the day.) We sometime got a watery soup usually made of potato peelings.

Sometimes, we got nothing. In the evenings (If we were in camp) we got a bowl of soup and a

slice of bread. The bread was awful and actually consisted of 22% sawdust. It had a bitter taste

and I have not liked brown bread to this date. On Fridays, we got the bread and a slice of

Bloodwurst. It looked like raw meat but wasn’t too bad. Sometimes we got barley soup which

was thick and good. This diet was barely adequate to keep you alive and everybody lost much

weight. What we really lived on was Red Cross Parcels. These were made up in the U.S.,

Canada and sometimes Australia. We were supposed to get one parcel per week. We actually

received one parcel to be divided among seven men. All the cans and packages were opened to

discourage hoarding for escape attempts. The packages usually contained canned meat, raisins or

prunes, crackers, canned butter, jelly, powdered milk, candy bar and cigarettes. The cigarettes

were the medium of exchange in Germany and could be used for bribes and food. It was difficult

to acquire an unopened pack of cigarettes. They were worth their weight in gold (Or Bread).

The dividing up of the package was a long and careful process. We would even count the

individual raisins. Food was the main topic of conversation. Everybody planned to run a

restaurant or grocery store when they got out of the Army. When we went on work details out of

the camp, we were usually fed a nourishing bowl of soup. This was usually in Munich but could

be anywhere in the nearby towns.

CAMP ROUTINE

Every morning, usually around 3:30 to 4:00 A.M., we were called out of the barracks and lined

up to be counted. “Charlie,” the guard who had this duty was a close copy of Colonel Klink of

TV fame. He rarely completed the count successfully. He became enraged when he failed.

Mostly he was O.K. To make sure everybody left the barracks, another guard with two vicious

dogs would turn the dogs loose in the barracks. It the dogs found no one, the guard would then

enter the building and inspect it. In my memory, no German entered our barracks unless it was

empty. If any of the prisoners were too sick to come out for the count, we carried them out. I

feel sure the dogs would have killed anybody left in there. There were supposedly a hospital and

doctors to treat any of us who were too sick to work. The few who did sign up for sick call never

returned to the barracks. We don’t know what happened to them. They may have been assigned

to another group but I wasn’t curious enough to get sick and find out. After the morning count,

we returned to the barracks long enough to get the hot tea, gather into work groups assigned and

went back outside to be counted again and marched to the train station. We usually went to

Munich. This took several hours as it was slow going. This routine was almost every day

including Sundays. I don’t remember the time we arrived back at camp but it was always well

after dark.

Camp life was neither dreadful nor pleasant. I guess it was best described as uncomfortable and

boring. It also smelled very bad.

Interrogations

The troops who captured me asked no questions that I remember. When questioned at

Ludwigsburg, they told ME my division and company. They were mostly interested in my

French medal and did not seem to believe me when I told them I found it. They laughed when I

said that. I think that medal caused me to be singled out on various occasions.

At Dachau, I was questioned in French and had to retell the story of the medal. They

were making sure I was an American soldier, I suppose.

At Stalag VIIA, I had an unusual session with a questioner. I was called from the

barracks by name (Unusual) and taken to a part of the camp I had never seen before. To me, it

looked like a western movie set with board sidewalks and false front buildings. The guard took

me up narrow stairs to a room on the second floor and told me to wait. He left. There were two

chairs and a table with several pamphlets. I read these. They were propaganda stories about

Jews. It reported in great detail how Jewish children are taught that it is all right to steal from

non jews and many other things along that line. Being young and stupid, I believed some of it

but most was obviously outrageous. After about 30 minutes, the questioner arrived. He was very

friendly, knew my unit and seemed to know that I had been at Okla. A&M. He said he had been

in Stillwater and knew the country well. He did not ask me any military questions but the subject

of the medal came up again. He asked me if I thought we would win the war. He seemed

genuinely surprised when I said yes. As far as I know, I was the only one in the barracks to be

questioned at that place in that manner. This was soon after the “Battle of the Bulge.”

Remembered Happenings

Christmas: We didn’t work that day. We gathered around the English Sergeant and listened to

his war stories. He was captured in Africa. He thought we were going to beat him up and was

greatly relieved to find out otherwise. I was in favor of the beating as he seemed to rarely be on

our side.

Early January: Many new prisoners arrived in camp. Most were from the 106th division who

were captured during the Battle of the Bulge. News was hard to come by and we hung on every

word they had to say. It was not encouraging. It looked like a long war. The Germans we talked

with were very animated and encouraged by this.

Often: When Munich was bombed, we could feel the ground vibrate in the camp. The distance is

about 40 miles. Bombers rarely overflew the camp. If they did, we were not allowed out of the

building.

Roof Repair: While working in Munich, I was assigned to lay tiles on the “New City Hall.” The

German name for it was something like Rathaus. This is a famous and ancient building which

has moving statues that come out of a clock. The tiles were broken mostly from falling

antiaircraft fragments. Most of the bomb damage had been repaired when I worked on it. The

building is about 15 stories high with a very steep roof. I was working up there one day when we

had an air raid. To get off of the roof you had to crawl up to the crown, go through a hole and

climb down a series of wooden ladders. I made it in record time. I also worked on the roof of a

church across the square. It had and even steeper roof and had no wall around the edge if you

slipped. Scary.

Landshut: This was a beautiful and quaint town east of Mooseburg, almost in Czechoslovakia. It

had never been bombed as far as I know. We went there occasionally to unload Red Cross

supplies for the camp. Landshut seemed to be a gathering point for bomber raids on Munich.

They would gather overhead, get into formation and proceed toward Munich. The Air Raid

Sirens were generally ignored because of this. On one memorable day, this changed. The

bombers formed up further out than usual and then proceeded to come at us aligned with the

railroad tracks where we were working. When the lead plane dropped a smoke bomb, we knew

we were the target. The guards took off running and we did the same. This was an extremely

accurate bomb run. Almost no damage was done to the surrounding buildings but the rail yards

were turned into a churned up mess. My immediate group had no serious casualties but the

bomb blast blew me through the air, ripped my French Overcoat (Again) and blew my glasses off

my nose. I caught them in midair. It all seemed to happen in slow motion. We returned there

the next few days to repair the damage. There were boxcars standing on end, completely under

ground level. I have never seen such thorough devastation. A German hospital train was on the

tracks at the time and virtually all the occupants were killed. The smell was as bad as you might

imagine.

Fred Sollars, a friend and coworker of mine at Humble Oil & Refining Co. was in Air

Corps Intelligence and was responsible for planning that raid. He said the train was the target

and they had reliable information it was a munitions train and had been painted with the red

crosses as camouflage. The Landshut rail center had not been bombed before because of its Red

Cross connection. He felt the Germans were misusing the area, (Thus the bombing) I saw no

sign of any munitions or other weapons in the debris we worked on. Sollars refused to believe

me and was very incensed with my remarks. I dropped the subject as he was my boss at the time.

One happy thing occurred on this outing. A wrecked box car was leaking a fluid that

turned out to be condensed milk. We ate it until we got sick and filled up our canteens with it to

take back to camp. We mixed it with snow and made ice cream. Some of the guys had jelly left

from their red cross ration and mixed it with the milk to make even better ice cream.

*****

While digging a ditch with many other prisoners just outside the outer fence of Stalag

VIIA, I made the mistake of laughing at a guard who was totally bald. He was mad at something

and his head was amazingly RED. He saw me and ran over and knocked me down with his rifle

butt. He would have hit me again but a very large prisoner (a black man) stood over me and the

guard backed off. The black man was not from our barracks but I certainly appreciated him. I

refused to go to the hospital as was suggested. I was not hurt bad. This was the only instance of

personal cruelty I suffered and I probably asked for that. There were many instances of

impersonal cruelty.

******

Interesting People: