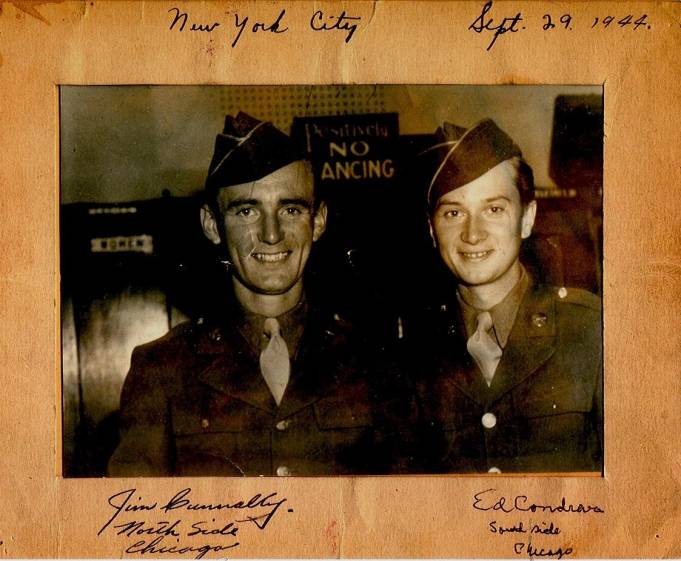

JAMES

CUNNALLY – G-Co, 411th

FINDING OUR

FATHERS

August 20, 2008

Patricia Lofthouse

We came in search of our fathers, my sister and I. Technically, I should call Diane my

half-sister, but we’ve never felt that way.

My dad, James Cunnally, was the only father she ever knew. Her own was killed in action on December 15,

1944, in the Vosges Mountains on the Climb to Climbach in France. The Germans hailed bullets from the hill

above and Dennis Zaboth was hit in the leg. My father pulled him by his side and

immediately sent a signal to the medics because he was the Radio Man of Company

G, 2nd Battalion, 411th. He

asked them to have a blood transfusion ready, but when he looked over at his

buddy from Chicago -- the one with a beautiful wife and new baby daughter

waiting for him at home – he saw in his friend’s eyes a vacant stare that told

him he would not be returning to them. He died in my father’s arms.

We came in search of our fathers, my sister and I. Technically, I should call Diane my

half-sister, but we’ve never felt that way.

My dad, James Cunnally, was the only father she ever knew. Her own was killed in action on December 15,

1944, in the Vosges Mountains on the Climb to Climbach in France. The Germans hailed bullets from the hill

above and Dennis Zaboth was hit in the leg. My father pulled him by his side and

immediately sent a signal to the medics because he was the Radio Man of Company

G, 2nd Battalion, 411th. He

asked them to have a blood transfusion ready, but when he looked over at his

buddy from Chicago -- the one with a beautiful wife and new baby daughter

waiting for him at home – he saw in his friend’s eyes a vacant stare that told

him he would not be returning to them. He died in my father’s arms.

My dad had to lay his friend down

and resume firing his Browning Automatic but he soon paused to throw up. He cried every night for the next six

weeks.

We knew it was their unit because we saw

it inscribed on her father’s tombstone in Irving Park Cemetery in Chicago. Our mother, Lorraine, brought her late

husband’s body home in 1949 when our government offered free transport of all

of the GIs’ bodies. My sister even

remembers the cold and rainy funeral at his gravesite although she was just 6

years old.

My father was there. He had returned from the war in 1946,

stopping first at the neighborhood tavern in his uniform when he got off the

bus from his release through New York and then Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. The bar owner offered him a free drink. This was the only thank you he ever

received.

He had liberated a concentration

camp in April. The German 19th

Army surrendered to the 103rd Division on May 5 at Innsbruck,

Austria, but my dad didn’t have enough points to leave Europe when the war

ended there. He stayed to relocate Russian and German POWS. During the height of the Cold War, he

casually mentioned how the Germans had warned him to be careful of the Russians

– that we would be at war with them in ten years.

He had written out mother to tell

her what had happened that night of December 15th and then called on

her to deliver his late friend’s personal effects. He had met her once when both soldiers were on leave from Camp

Claiborne, Louisiana. He had seen her

again when she visited her husband with her daughter and mother-in-law at their

second camp at Camp Howze, Texas, before they were shipped from New York City

to Marseilles. They had even double dated.

Once my father arrived now, he never really left. Our mother felt that in some way a piece of

her husband had been returned to her.

My dad served as a pallbearer and

held my sister at her father’s grave.

He took her home to our Italian grandmother’s house on Kildare Avenue

where she and our mother lived, and read the comics to her as he held her on

his lap. My sister remembers the happy

sound of the rustling of the newspaper as he unfolded it and the distinct smell

of the newsprint of the funny pages.

Not all of my sister’s lap

memories are happy, though. Our mother

learned that she had become a widow while seated at the piano while holding

her. The doorbell rang and our mother

hesitated a moment before lifting the two of them from the bench. When she opened the door, the Western Union

messenger handed her the telegram. She

cried out, but, being the woman that she was, did not scream.

From that moment on our mother did

not go out socially. She continued to

work while our grandmother babysat so that she could support her now all-female

family, including her disabled older sister. Her in-laws became so concerned

about her that they urged their own daughter to bring our mother out to the

Green Mill nightclub on Broadway Avenue where their son-in-law played in a

band. These same in-laws were joyful

when they learned that my father was coming round.

My father’s own mother, my

Norwegian grandmother, was not so thrilled.

A widow with a child, she worried?

She had lost my grandfather in April of 1944 and my dad as well as my

uncle, who was fighting in Europe as a Ranger, were not allowed to come home

for the funeral. Her oldest daughter had married and moved to Atlanta. My grandmother was left alone to raise a 12

year old son and an 18 year old daughter.

My aunt was staying out late and running a bit wild; my young uncle kept

running away. My grandmother had hoped

that my father would become the man of her unhappy house.

A

forty-year-old man named Zack Sigler had created two rooms of photographs,

books and research about the 103rd.

His passion began when he found a photo of his namesake, Uncle Zack

Sigler, who was killed in action on December 2, 1944, in France. The younger Zack had written to the National

Archives in St. Louis to obtain his uncle’s service record, and then found links

online to all of the books, newsletters and groups related to the Cactus

Division. He spent four days in St.

Louis searching and printing from microfiche all of the issues of the

newsletters from their camps, The Camp

Clarion Ledger and The Howitzer

from Camp Howze, Texas.

Zack painstakingly skimmed the

photocopies and as he combed through the headlines, he suddenly handed us two

articles. The Howitzer mentioned my sister’s dad! Apparently he was a star basketball player and helped his team

win several games. We never even knew

that he played a sport. Suddenly his

humanness became palpable -- a young man playing one of the great American

pastimes, not knowing, thank God, that in just a few short months he would be

dead.

I held the articles and my hands

shook. It occurred to me that perhaps

we could track down his yearbook from his high school in Chicago and learn even

more about him. All we had were the

letters that he wrote to our mother – letters that were about her and my

sister, not about him.

We found one – ninety year old Hank Pacha from Springfield,

Illinois. He remembered the liberation

of Landsberg, a sub-camp of Dachau. As

I sat with him on the bus, he told me nothing of his rank or his role in the

war, so like The Greatest Generation.

When I returned home I received a note from him with a letterhead that

read Brigadier General Henry F. Pacha.

We also met Jerry Brenner who

remembered everything. He told us of

the cold on the Climb to Climbach that December 15th, the day of greatest

casualities for the 103rd.

He reminded us that the Cactus Division engaged in 34 battles from

November of ’44 to May of ’45, fighting 500 miles through France, Germany and

Austria to the Brenner Pass in Italy.

He related how they crossed into Germany on December 16th,

one day after my sister’s father was killed and advised that the name of the

cemetery in France where he would have first been buried was Epinal. Mr. Brenner enlightened us that the

concentration camp that my father helped to liberate on April 27, 1945, was

called Kaufering, near Landsberg, Germany, and was a sub-camp of Dachau, and

that the German 19th Army surrendered to the Division on May 5,

1945, at Innsbruck, Austria.

The time came alive for us.

We began to understand why our

dad, for the rest of his life, could not stomach the thought of eating Spam,

because he had lived on it for almost a year.

We tasted the Cognac he drank

while getting “lost” in a French wine cellar for three days during

house-to-house combat.

We heard the giggles of the French

girls who gladly gave our father their full attention when he showered them

with Lucky Strikes, Hershey bars and the most coveted gift of all – a

regulation brown wool Army blanket. The

women tailored them into warm and beautiful coats.

We smelled the blood of the young

German whose ear was cut off by a member of the battalion, then handed back to

him with the advice, “Give that to your Feuhrer.”

We felt the rage when our father

reached Hitler’s bunker and proceeded to relieve himself on it.

We saw the sadness when he

approached the concentration camp where shadowy figures hid behind the doors,

shivering in fear but finally emerging as walking skeletons after they heard

the Yanks yell “Americans.”

Yet this man and another named

Wallace Morgan of Blyth, California, who was captured, beaten, thrown down

stairs, forced to forge rivers carrying German wounded and then getting

frostbite, and held as a POW for over a year, came back and fit in. They got their educations on the G.I. Bill

and made lives for themselves and their families. “The G.I. Bill was the best thing to happen to America,” he

opined and we all agreed. How did our

father’s life turn out so differently?

It was only when we met another

child of a deceased veteran that we learned about those who never connected

with normalcy again. A tall and thin

baby boomer from Massachusetts confided to me how he had lived a privileged

life as the son of a man who inherited a prosperous family lumber

business. Yet he detailed how after the

war his father left his mother with four boys to run off with her best friend,

the Godmother of one of their children.

The father stayed in touch with his sons, to have them touch hot

electrical wires to “toughen” them. The

deep circles under the handsome man’s eyes mirror my own, a telltale sign of

his depression.

In a strange way I breathed a sigh

of relief: ours was not the only father

who returned unwhole to live life on the edge:

His threats of suicide when he

gambled away every penny so sometimes there was no food for us to eat when the

little grocery store owner down the block on Sheffield Avenue had to cut off

credit to our mother;

how the neighbor upstairs offered

to give our mother some oil for the kitchen stove to heat our four room

apartment if she would give him herself.

his job, when he could keep one,

as a policeman, a good cop who could think like a criminal to catch one.

his drinking every day -- Jim Beam

with a Pabst chaser,

his smoking non-stop -- Lucky

Strikes or Pall Malls, at least two packs a day;

his sadness every December 15th,

when he wondered why he had lived and my sister’s father had died;

his inability to sleep in a bed,

always napping on the sofa for just a half an hour and then waking with a

start, sometimes grabbing the loaded gun he kept under his pillow to protect

his family. Our mother finally made him

remove the bullets when she found our littlest brother waving it through the

air.

“C’est la guerre,” he would

repeat. That we only knew too well.

Is it no surprise then, why

neither this thoughtful man from Massachusetts nor I can sleep a full night;

how we wake with a start and have to maniacally work in helping professions to

keep ourselves from falling into the pit of our depressions? Or why my two younger brothers often laid

stoned on the sofa, with an inability to search for work or find any semblance

of a normal life?

As we think of all of these

survivors of WWII, we know that the numbers reported are not the real

numbers. The casualties of war are

tenfold because it is every family member – the wives, their children, the way

their children relate to their own spouses, and even the unborn grandchildren

of these veterans who experience the effects of war. We know we will never let

our kids or our grandkids forget their grandfathers’ sacrifices, or their

grandmother’s. Her enduring love, work

and commitment throughout a very difficult life with two soldiers are perhaps

the greatest example of The Greatest Generation.

Jim Cunnally & Ed Condreva