103rd Cactus Division

|

103rd Cactus Division |

|

James Mulligan |

410th Company L

|

Shortly

after I reached my eighteenth birthday, I was inducted into the U.S.

Army. My basic training was in a motor mechanics school. After

completing basic training, I was sent to Fort Mead in Maryland to be

shipped overseas as a replacement. While there, those of us who werenít

19 yet were taken out because you could not be sent overseas as a

combatant younger than 19.

After

being sent to another camp temporarily, I was sent to join the 103d

Division in Texas. I was assigned to the motor pool as a mechanic. Then

one day the captain from the motor pool advised me that the motor pool

was over-strength and that I would be sent to a rifle company until we

were overseas and then I would return to the motor pool. I was never

returned to the motor pool. As I had never had infantry training, I was

at a disadvantage.

The

division sailed to Europe on troopships in October 1944. After a brief

stay in Marseilles, we were moved to the front lines and relieved the 3d

Division. We relieved them in the middle of a very dark night. The 3d

division had just captured that position that day. When daylight came, I

was shocked to see four dead Germans sprawled about the building. We

were told there was a dead GI in one of the foxholes outside. He ran for

his foxhole when mortar shells were coming in and one landed in his

foxhole.

We held

that position for about five days with very little food and being under

German mortar fire as we moved about outside. The people in the grave

detail would not come to the front lines to pick up the dead GI. So we

improvised a litter and carried him back. The stench of that body stayed

with me for a long time.

On the

fifth day at dawn, our other regiment attacked through us and across an

open valley.[1]

All hell broke loose. They were covered by artillery, mortar, and

machine gun fire. After their attack, the valley was littered with

killed and wounded GIs. That was my baptism into combat. I was scared

stiff seeing all of these soldiers under fire and the mortar and

artillery being shot at us.

We

continued to advance through France and I was amazed at how hardened a

person becomes to seeing people killed and wounded and just moving on.

In one incident just at dusk, we were attacked by mortar fire and

Sergeant Korte was running back to his foxhole when a mortar shell

landed right behind him. He was wounded very badly. There was an aid

station not far away; so we improvised a litter and carried him to the

aid station. By that time, it was very dark. I was at the right rear of

the litter and I knew he was dead. His foot was just dangling and I had

to keep putting his foot back on the litter. When we got to the aid

station, he was pronounced dead. A few years ago, his nephew called me

and asked if I knew what happened to his uncle. I became very emotional

and could barely explain to him what had happened to him.

There

were others killed and wounded along the way, but another traumatic

incident happened on January 25, 1945 at a village named Schillersdorf

in Alsace. It was bitterly cold and our company was dug-in in foxholes,

in battalion reserve outside of Schillersdorf, when German SS overran

the battalion that was holding the village. At dawn on January 25, 1945,

Lieutenant Raith ordered us out of our foxholes and to fix bayonets and

to retake Schillersdorf. As we moved across the valley toward the

village, we came under rifle fire. But we all made it into a courtyard.

There were probably about twenty of usóall that was left of our platoon.

As we all ran in single file across a street, each one of us was shot at

by the Germans. But we all made it into another courtyard. Some of the

men went behind the barn. One of them was shot in the forehead and died

instantly. Another was shot in the hand, another in the leg.

I

also went behind the barn, but was not hurt. I went into the house where

our lieutenant was with one of the wounded. Then Harold R. Carlson and I

in the lead headed back through the courtyard into the field behind the

barn when a tank shell landed, blowing my steel helmet off. I looked

back and Harold was down and I knew he was dead.

I

continued on to behind the barn and saw a column of tanks and infantry

coming our way. So I hurried back into the house to tell Lieutenant

Raith what I saw. He decided for us to retreat. So we took our wounded

and left Schillersdorf, leaving our dead behind.

No one

else knew what happened to Harold. To this day, I regret that I didnít

go back and make sure he was dead. I am the only person who knows how he

died and I wish I could have told his parents.

One of

our other platoons tried to retake the village from another side, but

they were pinned down on a hillside. I donít know how many escaped from

that ordeal, but I heard that some that were wounded froze to death

because no one could come to their aid.

The

front lines just set still for quite a while. Then on March 15, 1945,

our whole front line started a massive attack supported by a huge

artillery cover. Our battalion followed another battalion for a couple

of days. Then we relieved them in the middle of the night so we could

take over the attack. It was in dense woods and we were quite noisy. The

Germans could hear us and they kept shooting at the noise.

At

dawn, our captain told us to start the attack. I was the first scout and

I started advancing about 50 yards in front of my platoon. (The first

scoutís job is to draw enemy fire.) As I advanced along this heavily

wooded hillside, I could hear Germans talking, but I could not see them.

(I later learned that they were at a roadblock.) After a while, my

captain sent up word for me to stop advancing. At that time, a sniper

started shooting at me and barely missed. He kept shooting. I moved to

what I thought was a safer spot and that is when he hit me.

The

nearest village was Bobenthal, Germany. I still wake up at night with

thoughts that the sniper was just waiting for me to get a little closer

so he would have a better shot at me and I would be dead.

After I

was wounded, I spent about a year and a half in army hospitals. I still

take pills every night to ease the pain because of the wound so that I

can sleep.

The

time we spent in Europe was miserable. We slept in foxholes that filled

with water. The winter was the coldest that Europe had seen in many

years. It was difficult to dig a foxhole in the frozen ground. Our food

was K rations.[2]

I will never forget that experience.

Later,

when asked about my time in combat during World War II, I would become

so emotional that I would start crying and have trouble describing my

wartime experience. I didnít know what my problem was and why I would

start crying and shaking. It was very embarrassing and I thought I had a

mental problem.

Then

one day I went to see my service officer from the American Legion. That

person was not available that day; so, I asked the person on duty if I

could speak to him about the condition of my wound. After that

discussion, I told him I had another problem and I started crying. He

advised me to meet with a group of other World War II vets at a veterans

center in Dearborn, Michigan for counseling. I have been going to that

vet center for about four years and I find some comfort in meeting with

these World War II vets with similar problems with PTSD. |

||

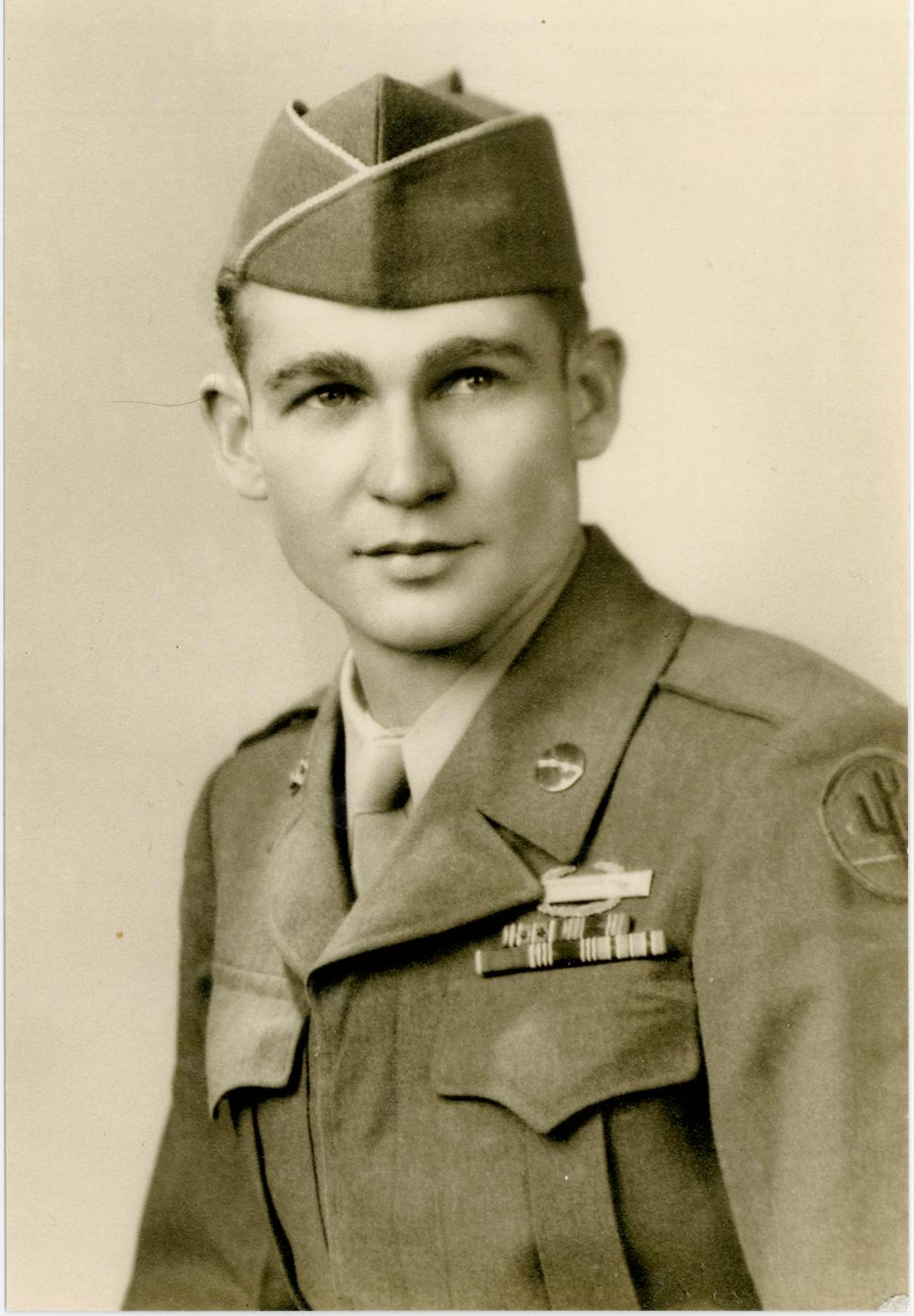

Home after the War |

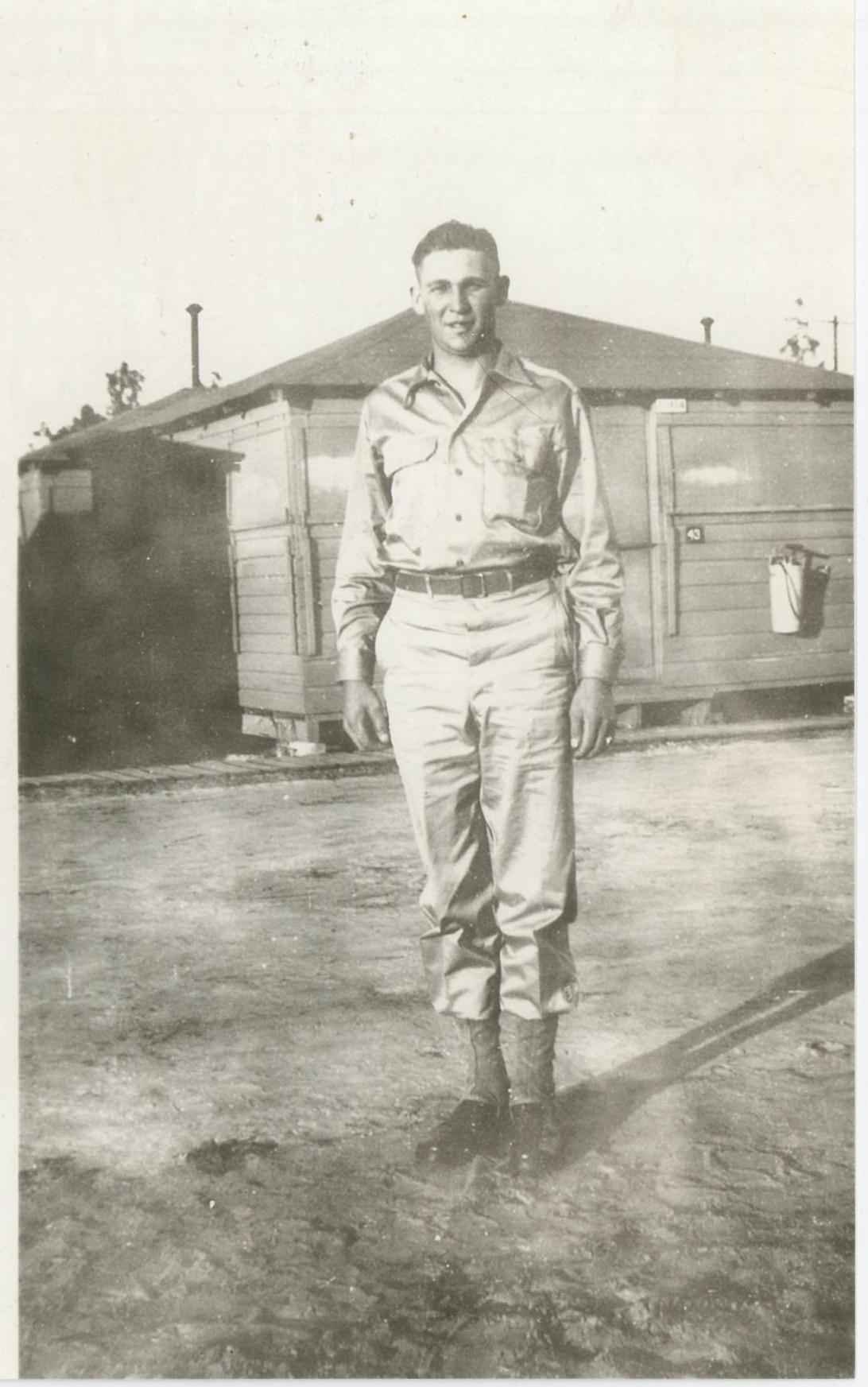

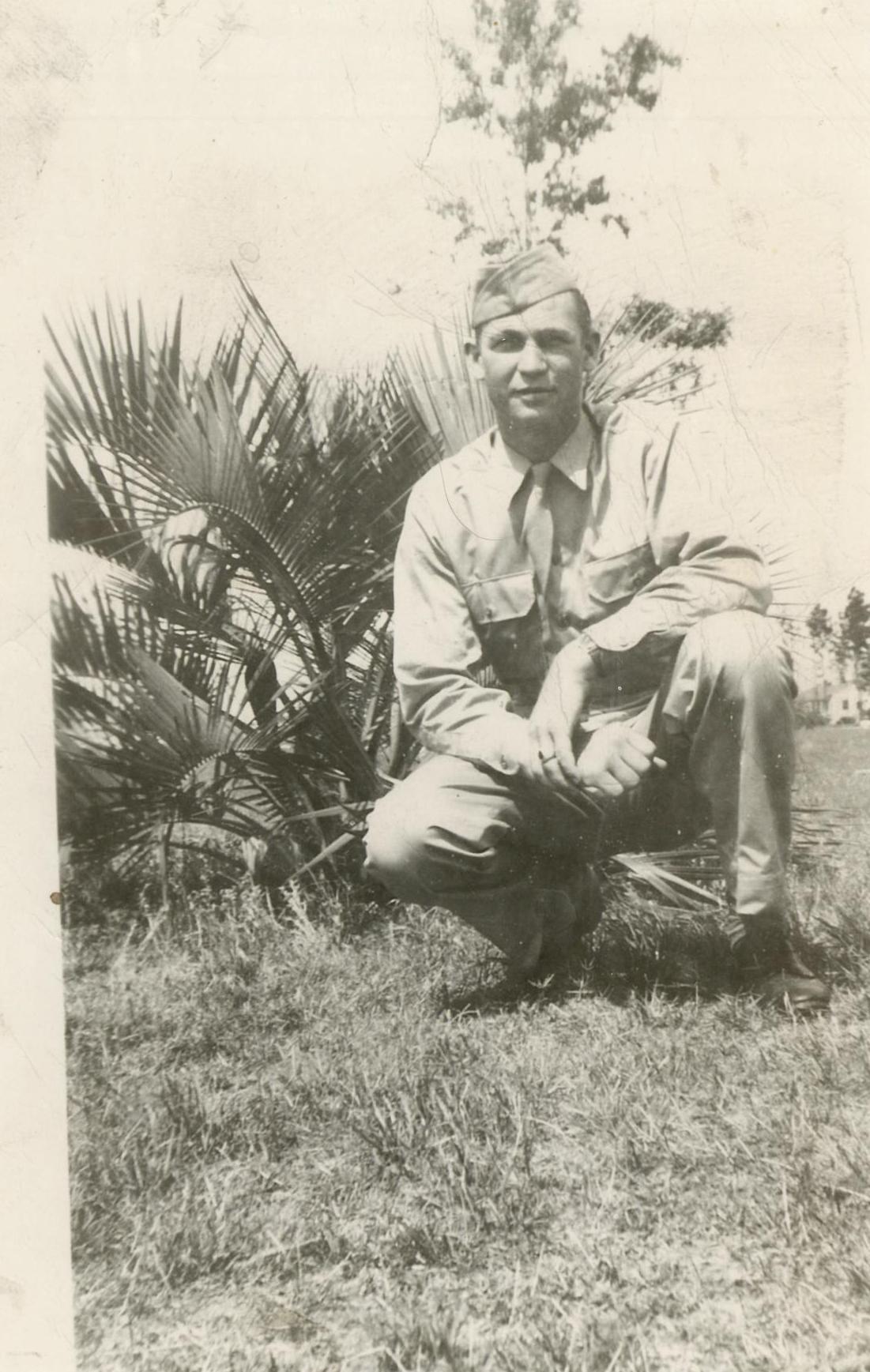

Basic Training |

|

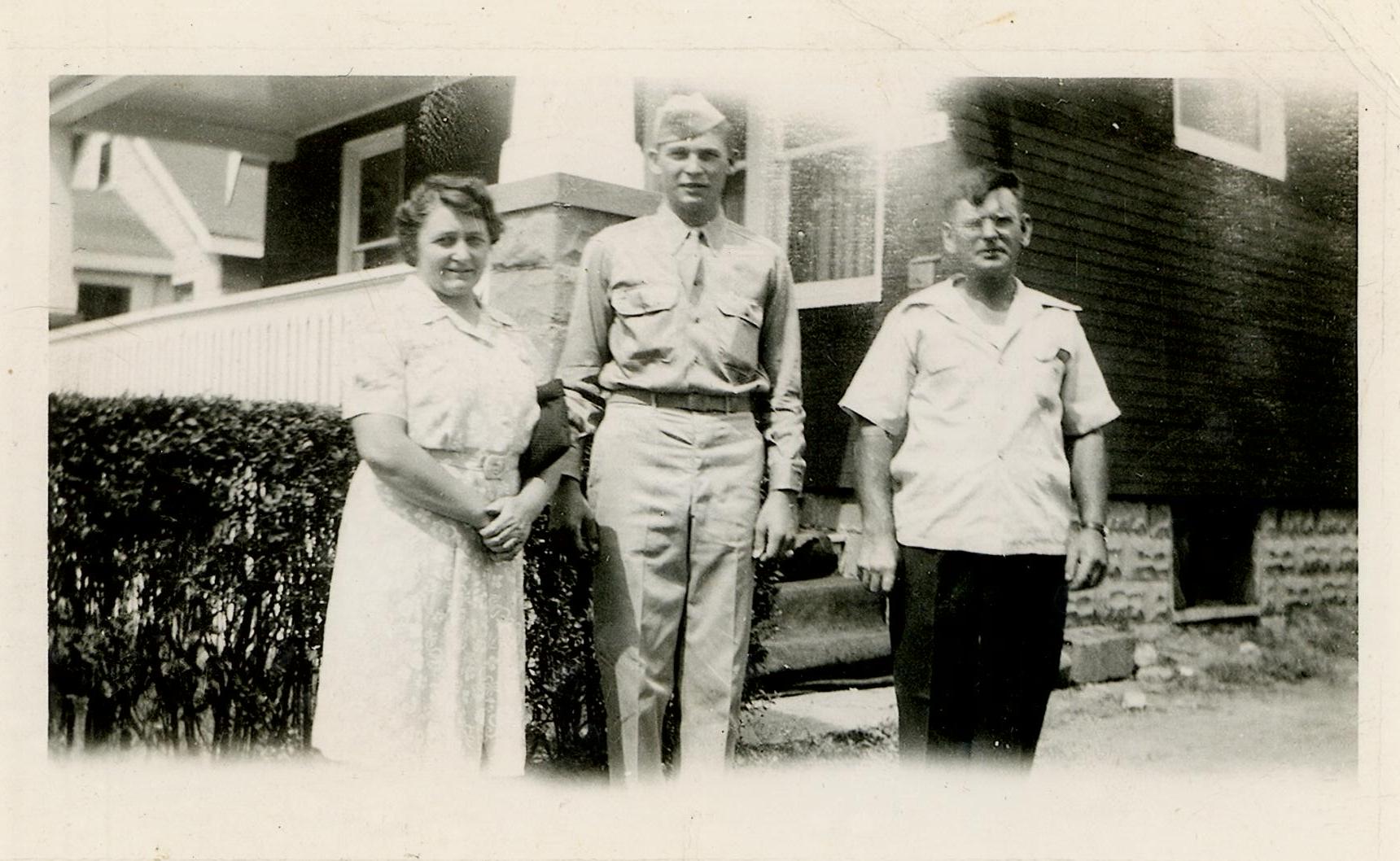

Home on Leave with Mom and Dad June 1944 |

||