|

Arlie

Avan Gray

|

|

|

|

September 2, 1918-August 17, 1967 |

- Rosemary, Judy, and I called him “Pop” or “Papa.” His step-grandchildren called him “Paka”, a pronunciation by

- Judy’s son, Tim, when he was first learning to talk. He became part of our family in 1950 and was with us only

- 17 years before his untimely death. During that time, we knew little about him. He did tell us that he served in

- World War II, that the Germans captured him, and that he spent the remainder of the war as a POW. He told us that

- he had been force-marched from one camp to another during a blizzard. Pop also told us that a Russian tank outfit

- liberated the last camp he was in and that Russian women drove some of the tanks. Mom mentioned that he had been previously married, a fact that was documented on their marriage license. He told us that he played basketball in

- high school. We knew that he grew up on a farm. Still, all these “facts” were nothing more than “bullet statements”

- and there was a lot about his life that we did not know. While Rosemary had memories of our father, Judy and I

- did not. Pop was the only father we remember. In researching the family history, I realized that the information on

- him was sketchy, to say the least. If I had no other reason to document his life, other than that he was an important

- part of our lives, he certainly deserved to be honored for his service during World War II. He was a member of our Country’s greatest generation

|

- Arlie, the fourth of five children (Ivan, Eva May, Cleva, Arlie, and Edwin) of Arley and Grace Harris Gray,

- was born in Lancaster, Missouri, on September 2, 1918; he was named after his father, but his family called him

- Avan. While in high school, Arlie was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. His pain didn't slow him down, though,

- as he played basketball for his high school team that was ranked number 1 in the state his senior year. Upon graduation,

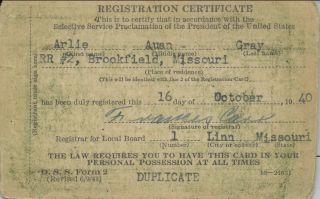

- he farmed with his father. On October 16, 1940, not long after his 22nd birthday, Arlie registered for the draft at the

- Linn County Selective Service Draft Board in Linneus, Missouri, and received his registration certificate. This card

- lists his height at 5 ft. 10 in. and weight at 191 lb. Prior to his registration with the Selective Service, he spelled his

- name Arley, as did his father; the draft registration clerk spelled his name Arlie, a spelling he would use for the rest

- of his life. On June 2, 1941, the Linn County Selective Service Board notified him that he was classified 4-F.

- During World War II, this classification was given primarily for muscular and bone malformations, hearing or

- circulatory ailments, mental deficiency or disease, hernias, and syphilis, and resulted in deferment from the draft.

- Arlie's classification undoubtedly was based on his having rheumatoid arthritis. Despite his deferment, he attempted

- four times to enlist in the Army; each time he was rejected. Meanwhile, Arlie fell in love with a young woman named

- June Moore. On November 27, 1942, he received a draft notice that directed him to report for induction into the

- U.S. Army. Four days later, Arlie and June were married in Brookfield, Missouri. June had a daughter, Mary Lou

- (from a previous relationship), and the two lived with his parents during his time in the service. A Certificate of

- Military Service indicates that Arlie began his Army service on December 5, 1942. Most likely he was transported

- to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis; other records indicate he received his initial basic and advanced infantry training

- at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. He was assigned to Company D, 1st Batallion of the 409th Infantry Regiment,

- 103d Infantry Division. A photo taken of Company D, during the summer of 1943, shows that he had been

- promoted to Private First Class. In November 1943, following training at Camp Claiborne, the Division moved to

- Camp Howze near Gainesville, Texas, where Arlie was a member of the cadre who helped train incoming conscripts.

- Arlie was most likely promoted to Corporal before his unit moved to Camp Howze, for the camp newspaper shows

- he was promoted to Sergeant in February of 1944; here, he was also awarded a Good Conduct Medal the

- following month. From Camp Howze, the division was transported to Camp Shanks, New York, pending

- deployment to Europe.

|

- The 103d left New York aboard an assortment of ships on October 6, 1944, and landed in Marseille, France,

- on October 20, under the cover of darkness. After assembling in a staging area north of Marseille, the 103d relieved

- the 3d Division at Chevry on November 8. Arlie was a squad leader in the 1st squad of the 1st platoon, a

- heavy-machine gun (.30-caliber water-cooled) squad. The 103d saw its first action against the Germans west of

- St. Die on November 16, in its drive through the Vosges Mountains through Steige and Dambach la Ville and

- onto the central Alsatian Plain

|

- On the evening of December 1 at about 9 p.m., Company B of the 1st Battalion, 409th Infantry Regiment,

- accompanied by the 1st Platoon of Company D, was ordered to enter Selestat to capture and occupy some houses

- on the city's outskirts (they also captured 80 German soldiers). Supposedly, this was to prevent the Germans from

- crossing the bridge to attack the bulk of the regiment, which had stopped short of the Giessen River Bridge leading

- into Selestat and was scheduled to launch an attack on the morning of December 2. The soldiers occupied six houses

- about 30 yards from the bridge. All was going well until about 3:15 a.m. on the morning of December 2.

- Don McGregor, a member of Arlie's squad, remembers the battle:

|

- I was in

the first house on the right hand side.

We wouldn't have any tanks until the next morning.

We were all right

- for six

hours. Then we heard some

tanks fire up. We didn't

have any bazooka ammo. We

were defenseless against

- tanks.

The tanks came down the street and parked in front of the

houses. The first thing

the lead tank did was blow

- up the

bridge. We were trapped!

After they blew up the bridge, they turned their 88-millimeter

guns to the houses.

- They were

sitting point-blank at curbside and we were “sitting ducks.”

The first shot from the tank blew apart my

- machine

gun. The second shot blew

a hole in the back of the house.

Then the tanks blew some timbers from the roof.

- I was

dazed and wounded by shrapnel. After

I came to, I looked for a way to get out of the house.

I noticed the hole

- in the

back wall toward the river. Four

others of my squad jumped out the hole and made it to the river.

I jumped

- out the

hole and was intending to run for the river, but I was too late.

German infantry were already standing

- there with

automatic weapons. Though

it seemed like an eternity, the one-sided battle couldn't have lasted

more

- than a few

minutes. Just like that,

I was a POW!

|

- As a result of that night's action, Company B counted 98 missing in action, 1 killed in action, and 2 wounded in

- action. Company D counted 18 missing in action, 9 wounded in action and 2 killed in action. The men would

- later learn that their opposition consisted of three divisions, one of which was a Panzer division; not exactly a

- level playing field for one company plus one platoon. When the tanks rolled down the street, Don McGregor

- remembers Arlie saying, “All right, everybody be quiet!” As the Germans began shelling the houses, quiet was

- something that could only be wished for. Most of the GIs in the houses were wounded, including Arlie who was

- hit by shrapnel in both legs as well as a bullet wound in one of his arms. Sgt. Elvin Beemer, a forward observer in

- Company D's mortar platoon, was also hit and knocked unconscious by the concussion from one of the

- German 88 mm shells that tore open the house. Don also remembers Arlie saying, upon observing the inert sergeant,

- “Oh, God, he’s gone.” Those few who didn’t escape were taken prisoner by the German infantry troops.

- Immediately after their capture, a mortar barrage hit the POWs and their captors. Just before all hell broke loose,

- Sgt. Beemer had called in the target; his mortar men had no idea that GI POWs were with the Germans at the time

- they let loose their barrage. Arlie and his fellow POWs were taken across the Rhine River and forced to dig gun emplacements for the Germans. They were housed in large stone barracks during this period. Then, by rail car,

- they were transported to Stammlager (Stalag) XII-A, a processing and distribution camp for Allied prisoners of

- war near Limburg, Germany; this journey took about ten days. His POW ID picture was taken at Stalag XII-A.

- The POWs remained there through Christmas[1] and, during the last week of that year, were then sent to the

- various POW camps to which they were assigned. Arlie and Sgt. Beemer were sent east to Stalag III-B,

- a camp for non-commissioned officers (NCOs), near Fuerstenberg on the German-Poland border. In January,

- the population of this camp was reported to have reached an estimated 5,000. The POWs were not at this camp

- for long, either, for on the evening of January 31, 1945, with two hours notice, the Germans marched the entire

- camp population westward, in face of the advancing Soviet 33rd Army, 1st Belorussian Front. It has been

- estimated that nearly 1,200 POWs did not survive the forced march to Stalag III-A.

|

- Conditions during the march westward from Stalag III-B were extreme, including subfreezing cold and blizzards, and

- from the sheer exertion required in the movement. Some of the prisoners were given old overcoats, but no one had

- hats, gloves, or boots. The prisoners were marched for 24 hours without stopping. Throughout the march they were

- given very little water and for two days they had no water whatsoever. Also, the prisoners received no food until the afternoon of the third day when they received one-fifth of a loaf of bread per man. For the entire seven days of the

- march, they were given 1-¼ loaf of bread per man and one-eighth of a #2½ can of cheese for eight men at one time.

- After seven days, and a 108-kilometer march, the POWs reached Stalag III-A, at Luckenwalde, which was about

- 50 kilometers south of Berlin. Most of the Americans who completed the march to this camp spent the remainder

- of the war here until liberated by the Red Army on April 22, 1945. One account of the liberation of this

- camp is as follows:

|

- The German guards abandoned the camp during the night. The next morning, somebody in our tent was up early,

- probably to check on the water tap. When he went out he discovered there were no guards, not even on the main gate.

- He came back to the tent hollering. Everybody ran out to look around. About 9:00 A.M., a Russian tank outfit

- came driving in. The tanks knocked the main gate down and then flattened the barbed-wire fences. One of the

- tank commanders, a Major, was a big husky woman, about 35 years old.

|

- Even though the camp was liberated, many of the American prisoners remained there and did not begin the

- repatriation process until May 6, as the camp was in territory captured by, and under the control of, the Soviets

- whose priority was annihilation of the German armed forces. Arlie’s whereabouts following his repatriation is

- unknown because his military records, as were countless thousands of others, destroyed in a fire in 1973. Thus,

- we will never know the exact nature and extent of his injuries nor where he served upon returning to the US.

|

- All

Prisoners of War were promoted one grade during their capture.

Arlie was a Buck Sergeant when

- captured

and was promoted to Staff Sergeant.

When liberated from the camps, all POWs were

- transported

to the "Cigarette Camps" around LaHavre, France, for medical

evaluation before being sent

- home

for 60 days furlough. At

the end of the war in Europe, all those soldiers who had earned

the

- requisite

number of “points” were returned to the U.S. for discharge.

Those who didn’t have enough

- points

were reassigned. Because

Arlie had been moved from one POW camp to another, his parents

- never

received notification of his prisoner status; they had only been

notified that he was MIA

- (Missing

in Action). However, his

sister, Eva, contacted the Red Cross, which confirmed his POW

- status.

Nevertheless, it was quite a shock to them when he showed up at

home. Following his

furlough,

- Arlie

was reassigned to Ft. Lewis, Washington not long after the war in the

Pacific had ended.

|

- Pop did not talk much about his service during the war. I don’t remember the exact question, but I must have

- asked him at one time if he was a war hero. He answered, "The real heroes of the war were those who gave their

- lives on the battlefield." He did tell some stories about his time in the POW camp, though. As the Allies advanced

- from the west and the Russian Army from the east, the Germans became increasingly nervous and agitated.

- When the US Army Air Corps P-38's (which the Germans called the forked-tail devil) and bombers bound for

- Berlin would fly over, the POW's would cheer. The camp guards tried to thwart any escape attempts by morning

- and evening roll calls in which everyone was required to stand outside of the barracks. When the name of a

- prisoner who was sick and couldn't be present was called, someone would yell, "Ein man scheissen" (I'll leave

- the translation of this phrase to your imagination). For the most part, old men guarded the camps, as able-bodied,

- younger men were needed on the eastern and western fronts. One of the old guards, who had apparently seen

- at least one western movie, would say, "Tom Mix", and then laugh heartily. The prisoners were fed a piece of

- bread and cup of thin soup (Pop called it grass soup) a day. When the prisoners were served meat in their soup,

- it usually was infested with maggots. For several years afterward, Pop would not eat meat or soup. Malnutrition,

- dysentery and, in some cases, wounds, left many of the prisoners in weakened condition. Camp conditions were

- deplorable, especially during the winter of 1944-1945, as the barracks had no doors and light could be seen

- between the exterior boards and often these buildings held more than twice the number of men for which they were designed. There was little the prisoners could do to escape the weather conditions. These conditions took their

- toll on his health and certainly exacerbated his arthritis. When repatriated from the POW camp, Arlie weighed

- 140 pounds. The horrors of his experiences in combat and in the camps left him with nightmares for years afterwards.

|

- Arlie earned the European-Africa-Middle Eastern Theater medal with three bronze battle stars (Alsace, the

- Rhineland, and Central Europe), a Bronze Star (awarded to those soldiers who earned the Combat Infantry Badge),

- and a Bronze Arrowhead[2]. Among his other awards was the Asiatic-Pacific Theater medal[3], the American

- Campaign medal, the World War II Victory medal, the Good Conduct medal, Combat Infantry Badge, and a

- Purple Heart. Later, all prisoners of war were awarded a POW medal.

|

- Arlie was discharged from Ft. Lewis on November 3, 1945. His sister and brother-in-law, Cleva and Pete Apel,

- drove north from Orchards to get him. June and Mary Lou joined Arlie and they lived with Pete and Cleva for a

- few years following his discharge. Here he found work with a construction company. Sometime during 1948, June

- left for Missouri with her daughter, saying that she was going to visit her grandmother; she never returned to

- Washington. Later, Arlie would find work as a welder at Peerless Trailers in Portland, Oregon. At Peerless, he

- worked with our family's notorious matchmaker, Uncle Fred Hargrafen (Mom's brother-in-law), who introduced

- Arlie to my mother, Rosabel. After a short courtship, the two were married in Orchards, Washington, on

- January 1, 1950.

|

- Camping trips to Spirit Lake (Mount St. Helens) and Lost Lake (Mt. Hood), fishing, and our 1952 trip to

- Iowa and Missouri in Pop's 1950 Ford sedan are highlights that I will always remember and cherish. I also

- remember him drilling us on our multiplication tables when Judy and I were in the fifth grade; he insisted that we

- learn these and we did (thanks, Pop). One of his favorite television programs was "Hogan's Heroes." I think there

- was something about the old German guard, Sgt. Schultz, which rang true with him. He liked to play cards with us,

- too. A favorite Friday evening activity was listening to the Friday Night Fights sponsored by Gillette. Saturday

- nights were spent playing Pinochle with Aunt Neva and Uncle Fred. Pop earned his Private Pilot's license courtesy

- of his GI Bill and took us kids flying, from Evergreen Field east of Vancouver, in an Aeronca 7AC Champion,

- a two-seater, fabric-covered airplane with a whopping 65 hp engine. Including taxi time, takeoff, and landing,

- Pop had just enough time in one hour (at $7.50 per hour) to take each of us three children up for a quick spin

- around the field; Mom never got to go flying with him. Pop was an Assistant Scout Master during my days in

- the Boy Scouts and he liked to hunt and fish. He was a crack shot with his prize 30.06 Remington rifle, which

- he bought in Iowa in 1952, particularly if the object was moving. On one hunting trip to Eastern Oregon at the

- start of my senior year in high school, he dropped three deer before the rest of us could get off a shot! He was

- also an excellent mechanic and kept my old cars up and running many times.

|

- In

1965, Mom and Pop moved from North Portland to Lake Oswego, Oregon,

where they shared the

- last

of their time together in a neat-as-a-pin home with a wonderful

flower-filled yard and no stairs.

- During

a union strike in the summer of 1967, Arlie suffered a massive heart

attack that took his life on

- August

17; Pop was 16 days short of his 49th birthday.

|

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The above narrative is based on a compilation of information from various sources, including that available

- through the National Archives, interviews with and correspondence received from members of Company D,

- 409th Infantry Regiment, Cleva M. Apel, the few items that were a part of Arlie’s service record, and (of course)

- my selective and fading memory. I am not a fan of Tom Brokaw, but he got one thing right in his book: Arlie and

- his fellow soldiers certainly earned the title of “our Country’s greatest generation.”

|

|

|

|

| POW ID Card |

Selective Service

Registration |

|

|

| Stalag XII-A |

Stalag III-B |

|

(L to R) – Leo Goldfarb (Acting

Cpl), Arlie Gray (Acting Sgt), Lloyd Lindblade (Acting Sgt)

[Notice that stripes are armbands]

|

|

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] On Christmas Eve, a bomb from a British Mosquito bomber inadvertently landed in the officer’s portion of Stalag XII-A and blew countless Allied officer POWs literally to bits. The German prison guards forced some of the prisoners to collect dog tags from the carnage, dig mass graves, and bury those who were killed.

[2] The Bronze Arrowhead is awarded to those who participated in an amphibious landing or parachute drop behind enemy lines. This decoration is an enigma because, so far as is known, Arlie did not participate in either type of operation.

[3] Undoubtedly this ribbon was awarded because of Arlie’s reassignment to a unit at Ft. Lewis that had served in the Pacific Theater during the war.

|